A month ago, I did a case study for a fellow FIRE planner (“John Smith”) and the reception was awesome. So why not do more of those? Without even asking for volunteers, I already got two more fellow FIRE planners who contacted me via email and shared their financial parameters. Today’s case study is for “Captain Ron” and, of course, Ron isn’t his real name, though he is indeed a Captain. Not the “Captain Ron” from the 1992 movie, but just a captain. More on that later!

Why are case studies so exciting? One of the most important lessons I learned from my Safe Withdrawal Rate research (jump to Part 1 of the series here) is that the safe withdrawal calculations are best performed on a one-by-one basis. As we pointed out in our post last week, a withdrawal rate strategy should respond to market factors like equity valuations and bond yields as well as personal factors like age, retirement horizon, and expectations about pension and Social Security benefits. Further complicating the whole calculation is also the fact that we all have different distributions of assets over taxable, tax-deferred and tax-exempt accounts. So, let’s take a closer look at Captain Ron’s situation…

Captain Ron’s situation

We’re aged 46 and 45 with the bulk of our saving occurring in 2006 forward (401k contributions started in 1993). We plan to leave work in Sept this year then travel to Florida where we’ll move onto a sailboat. We’ll live/sail the boat Dec-May and then when hurricane season rolls around we’ll store the boat and travel by land Jun-Nov. Both lives provide the opportunity to live cheaply or extravagantly and we’ll adjust as the budget dictates.

Wow! I love the sailboat part! We can talk about financial independence all day long, but FIRE on a sailboat is taking the “I” part of FIRE to another level!

I concluded a 3.25% withdrawal rate was pretty darn safe (100% when CAPE>30) using your downloadable spreadsheet and would feel OK going as high as 3.5%. Our new life will be drastically different than our current one so we have basically just said “we’ll make it work” even though we don’t exactly know our future expenses.

We plan to spend down the cash cushion, then transition to a variable withdrawal method based on (I hope) a future Big ERN post(s) about the subject that finishes up earlier discussions on the topic. Part 12 convinced me to change our plan away from the cash cushion.We’re renting the house for 2 years starting Oct 2017 and plan to sell in Apr 2020 therefore reaping ~550k in equity with zero taxes. We bought the house for 608 and should be able to sell for ~900 so all gains will be tax free.

The numbers:

- Cash: 92k

- Taxable investments (Vanguard): $799k. Cost basis is $570k and $229k is gains.

ESPP (hers): 16k- 401k: his: 816k, hers: 811k

- Roth IRA: his: 53k, hers 53k

- Pension (his, age 55, no COLA): 11k annually

- Pension (hers, age 55, no COLA): 14k annually

- SS estimate is for starting at age 67. I came up with 27k (him) 28k (her) starting at age 67.

Some additional back and forth yielded the following information:

- Ron and his wife already own their sailboat worth $140k and this figure is not included the above net worth figures.

- Ron and his wife plan to keep their current house and rent it out until early 2020. They budget an extremely conservative annual net rental income of $9k (after deducting all expenses) and net proceeds of $590k in 2020.

- Ron and his wife have a very equity-heavy asset allocation. Good for them! I’m sure the impressive multi-million dollar net worth is the result of that high equity share and sticking with equities through the mess in 2008/9 and the impressive recovery that followed.

Some preliminary observations

This is an interesting case study! The question is not whether Ron and his wife can retire. They are already steadfast in their plan to pull the plug in September and they simply wonder how much they afford to withdraw. They didn’t specify an exact budget but their massive net worth of about $3m provides plenty of wiggle room. It seems that they are mentally prepared for 3.25% but we will see if we can push that number a bit higher.

I also like the move to Florida from their current location. Ron didn’t specify from where he and his wife will be moving but it sounded like high-tax state. The zero income tax in the Sunshine State combined with generally lower living expenses is a nice example of geographic arbitrage.

One unique feature is that Ron and his wife like to keep their current house for a few more years. The house is valued at close to $1m gross and over half a million dollars net of the mortgage! For the record, I tried to talk them out of keeping the house initially because of the hassle of managing a property remotely while on the ocean and the risk of a lumpy concentrated investment. But I can also see that keeping the house isn’t a bad investment. The $9k p.a. of net rental income is not too different from the dividend income if they invested in an equity fund. And with a home price appreciation equal to only about 2%, levered up by about a factor of 2 you get to an equity-like return expectation. So, why not! If you have a trusted person to manage the house while you’re at sea, go for it! As long as you sell the house in time all of the capital gains in the house are tax-free (they are below the $500,000 per couple exemption if they lived in the house for 2 out of the 5 years prior the sale). The one caveat I want to point out is that rental income is taxed as ordinary income and will interfere somewhat with the Roth Conversion.

Calibrating the maximum initial SWR

I went back and forth a few times about what’s the best way to model the delayed sale of the house:

- Calculate the withdrawals as a % of today’s non-housing net worth. But account for the rental income and the home sale through the “supplemental income/expenses” feature in the SWR Google Sheet.

- Take the estimated proceeds of the house sale in 2020 and discount them by a reasonable rate (7%) to convert this future cash flow into 2017 dollars

I opted for method 2. Not that the calculations make that much of a difference, but I found that method more intuitive. If the market were to tank between now and 2020 we would not expect the house to fetch the same $590k net proceeds. My calculation would come close to assuming that the return on their home equity evolves roughly in line with the portfolio return.

So here it is, Captain Ron’s Net Worth: $3,135,187. Pretty impressive!

Taxable Accounts (Cash, Vanguard, ESPP): $904,000

Retirement Accounts: (401k, Roth): $1,733,000

Home Equity: $498,187 (=$590,000 discounted by 7% for 2.5 years. And I even disregarded the rental income, just to be on the conservative side)

I should say that discounting the expected $590k is purely for calibrating the maximum SWR. In some of the other calculations that follow below, I will again revert to the actual cash flow assumptions specified by Captain Ron, where the home sale occurs in 2020!

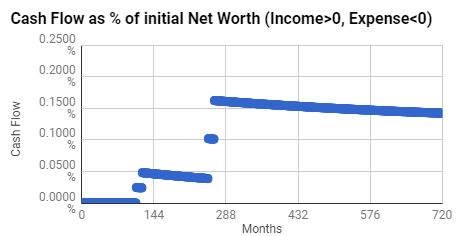

I applied a 15% haircut to the Social Security estimates: $23,800 (his), $22,950 (hers) to account for the uncertainty about future benefit reductions. I like to be super-conservative with this. Ron and his wife might be able to suffer much less of a haircut if they make it to age 55 without any major Social Security reform. Age 55 is considered the cutoff where politicians normally don’t want change the rules for folks too close to retiring. I also discounted the $11k corporate pension benefits by an inflation rate of 2% p.a., so the supplemental income per month as a % of today’s portfolio value looks as follows:

The 4 bumps are 1) Ron gets his pension after 9 years, 2) Ron’s wife gets her pension after 10 years, 3) Ron gets Social Security after 21 years and 4) Ron’s wife gets her Social Security after 22 years. Notice the slight decay in the (real) income due to the pensions losing 2% real purchasing power every year. SocialSecurity doesn’t lose purchasing power because it should still be inflation-protected.

For the SWR simulations, I assume an 80% Stock, 20% Bond portfolio, a 50-year horizon and a zero final asset target (no kids).

Check out the Google Sheet with the calculations and more info!

As always, when working with Google Sheet: I have to keep one clean copy posted on the web. Please don’t ask for permission to edit this file but rather download your own copy if you like to change anything: Click “File” -> “Make a copy” See picture on the right!

The summary of simulation results are below:

- Forget about 3.25%! A 4% initial withdrawal rate would not run have run out of money for a CAPE<30 in any of the historical simulations!

- With some flexibility in their spending, they can probably go all the way up to a 4.25% SWR (8.7% failure rate). That SWR would translate into a pretty impressive initial withdrawal amount: slightly above $133,000 per year, then adjusted for inflation every year, but also reduced exactly dollar-for-dollar when the supplemental cash flows (pensions, Social Security benefits) kick in.

But: don’t forget about income taxes! As we will see below, Ron will owe taxes on some of the withdrawals later during retirement when required minimum distributions kick in. To account for future tax liabilities, let’s take down the withdrawal amount to $120,000 p.a.

Dynamic Withdrawal Rules?

Since Ron hinted at it, a dynamic safe withdrawal rate rule I like a lot is based on the Shiller CAPE ratio. I looked at a few different parameterizations in Part 11 of the SWR series and found that the rule with a=1.5% and b=0.5 looks like a good compromise. According to today’s CAPE of 30 (the actual number is a bit lower, around 29.5, because Shiller is too slow in updating his earnings numbers, as we pointed out here), we are now looking at a SWR of 0.015 + 0.5*1/30=3.167%. That seems low, but recall that we have to account for the future pension and Social Security payments. One way to do this is to use the tables in Part 17 to translate future cash flows (real and/or nominal) into today’s adjustments to a SWR. I plugged in the values for Social Security and the Pensions and got an adjustment of 0.7% and 0.3%, respectively, for a total one additional percentage point in the SWR. How cool is that? You get the same ballpark number with the CAPE-based rule: Slightly above 4% total SWR. And going forward, simply use the formula SWR = 2.5% + 0.5 * 1/CAPE.

Asset allocation

I played around with the asset allocation a bit and found that 80/20 seems to offer the best probabilities of success. For the case study I performed at ChooseFI, 60/40 seemed more appropriate due to much higher expected Social Security benefits as % of the portfolio value and a time span between retirement and drawing benefits. Ron hinted at being quite comfortable with a high equity share, so I’m glad that I don’t have to talk him into raising his equity share.

A Cash Flow Problem?

A significant portion of the portfolio is tied up in retirement plans, especially the 401k accounts. The concern for the early retiree is that withdrawals might exhaust the taxable accounts before reaching age 59.5. To check if this will be an issue, let’s see how the different account balances evolve between now and the year 2031 when Captain Ron will be 60 and therefore eligible for penalty-free withdrawals from the 401k. To be precise, age 59 and 1/2 is the cutoff date, but to be on the safe side I use 60.

For the simple simulation, I assume the specified cash flows from the house transaction and the pension starting in years 2026/27. Let’s assume an annual consumption target of $120,000 and 6% annual returns ($30,000 in consumption and 1.5% return for the final quarter of 2017) and iterate forward the withdrawals (balances are for the beginning of the period, i.e., before withdrawals occur). See results below:

- Relying solely on the taxable account withdrawals should get you to age 60 (59.5 to be precise). It looks like you will tap your 401k penalty-free, though not tax-free!

- But this is still cutting it a bit short. If Ron and his wife want to purchase a house in Florida after a few years of sailing it could compromise this calculation. That’s something to keep in mind. Another reason to not go overboard (pardon the pun!) with the initial withdrawal amount!

The limited role of the Roth Conversion Ladder

Ron’s case is the picture-perfect example of when the Roth Conversion Ladder doesn’t deliver the promise of “never paying taxes in retirement.” The initial amount in the 401k is just so staggering, it’s impossible to transition over a meaningful amount to a Roth IRA over time. And forget about converting the entire 401k. To see how futile the traditional Roth Conversion Ladder is, note that the standard deduction plus 2 exemptions would be worth $20,800 p.a. in 2017. This is the amount you can transfer tax-free from the 401k to the Roth each year. But your $1.6m 401k portfolio will grow by an estimated 6% p.a., or close to $100k. The traditional Roth ladder can only somewhat slow down the growth of this potential future tax liability. Just to be sure: Being a 401k-millionaire a good problem to have, as my blogging friend Fritz from The Retirement Manifesto can confirm. But folks in the FIRE community also like to minimize taxes so this will take some additional hacking!

Why you still need the Roth Conversion Ladder

Let’s iterate forward the account balances to the year 2041 when Ron has to start taking required minimum distributions (RMDs). And his wife in the year 2042, see table below:

At age 70, the minimum required distribution is 3.65% (=1 divided by a life expectancy of 27.4 years, according to the IRS table III for Married Couples), so that’s a whopping $190k+ in annual and taxable withdrawals from the 401k starting in 2041/42. That withdrawal, combined with pension and Social Security income will reach way beyond the 15% tax bracket, probably deep into what would be the 25% bracket in today’s dollars and who knows what the rate and brackets will be in the future! (thanks to commenter omni for pointing out an error in the earlier version and pointing me to the correct IRS table!!!)

So, Ron should do the Roth conversion not just in the tax-free space (standard deduction plus exemptions = $20,800) but also into the 10% bracket (currently $18,650) and even into the 15% bracket. Since it’s already clear that future withdrawals will be taxed at 25%+ it’s a prudent move to do conversions even at a 15% marginal tax today! Let’s assume he does an additional $20,000 of conversions into the 15% bracket. That’s a total potential $59,450 in conversions per year (=20,800+18,650+20,000). Of course, we have to reduce that by the rental income and later by the pension income. Ron also has to make sure that the withdrawals from the taxable portfolio don’t generate short-term gains and the long-term gains and dividends don’t bring his total taxable income beyond the second tax bracket, where he’d have to tax his capital gains and dividends at 15% marginal. Given the substantial cost basis in your existing accounts and a large injection of tax-free money in 2020 that should be feasible, though.

Let’s look at the evolution of account values with the Roth Conversion. The conversions show up as “negative withdrawals” from the Roth and positive withdrawals from the 401k in the years 2018-2033. Starting in 2034, your taxable account is exhausted and you withdraw from the 401k, which ends the potential for any more conversions. But the Roth conversion did its job. You reduced a $5.2m balance in the 401k without the conversions to just about $2.8m and shifted that money into the Roth. In fact, your Roth is now almost as high as the 401k, how cool is that?!

How much does the luxury of shifting money to the Roth cost you? Not that much: You generate taxable income of $18,650 taxed at a 10% rate and $20,000 taxed at a 15% rate, so an annual tax bill of under $5,000 in today’s dollars for 16 years. But that affords you a much smaller tax bill at age 70. And who knows how tax landscape looks at that age. You might move to a different state again that, unlike Florida, taxes income. Doing the conversion at 15% marginal seems like a bargain in light of how high your future marginal tax might climb!

Conclusion

Ron and his wife are in excellent shape. Considering that their savings are mostly post-2006, their $3m net worth is very impressive! A withdrawal rate of 4% to maybe even 4.25% looks feasible in historical simulations. Since Ron seemed happy with a 3.25% SWR (around $100,000 in annual expenses), maybe he could shoot for that level early on and use the remaining $20,000 to pay for the Roth conversion ( about $5,000 p.a.) and keep the remaining $15,000 as reserves.

Wow, your work never ceases to amaze me, Big ERN. Thanks for the shoutout. It IS great being a 401(k) millionaire, but I face the same issue as Captain Ron on trying to get the before tax $ rolled over to a Roth. I’ll be paying a lot of taxes, and there’s no way to avoid it. Looks like I’ll be in the “same ship” as Ron. Maybe he’ll invite me sailing some day…..sounds like he’s got a great retirement ahead.

Thanks, Fritz! Exactly, there is no way to avoid taxes. Just try to minimize them by comparing marginal taxes across time!

Thanks for stopping by!

OMG, sell that house. 9K earning on 590K. That is what, 1.5% return, plus you have to worry about living in it for 2 out of the last 5 years in order to sell it.

Take the $$ now and put it into muni’s or something.

My exact initial reaction, too! But they will get less than $590 if selling today. There is a gain in home equity from a) slight appreciation and b) paying down the mortgage. The internal rate of return on keeping the house is not that different from most people’s equity expected return.

Hi Matt,

Captain Ron here. Yes I agree from a pure financial perspective it makes sense to sell the house. But we’re keeping it for a couple years to hedge against us not loving the sailing life and wanting to return. Once we sell it we’ll be priced out of returning to this town. We’ve set a deadline of 2.5 years to decide about selling or returning to account for the IRS tax rules.

Excellent point. Never forget about the large transaction costs of selling and then buying a house again. It’s an insurance policy of sorts.

Well… After reading this article and having a few more discussions with the wife we’re now switching gears. We’re going to attempt to sell the house. Thanks for the additional perspective that helped us come to this conclusion.

I’m strongly considering selling it myself (FSBO) so if anyone has any tips or lessons learned I’d appreciate the feedback.

Ha, just as I started to warm up to the idea of keeping the house! 🙂

Calculations for the SWR stay the same, though! Best of luck!!!

Matt and ERN, Thanks for your feedback on the house. It drove a hard discussion for us but eventually like I mentioned, we decided to sell. The transaction completed and we walked away with $575k after the dust settled. We’re now in Florida working on our used boat and getting it ready to launch. I’m also trying to get the courage to drop ~$550 into the market.

Wow, thanks for the update! Good luck with investing that big loot. Maybe try dollar cost averaging if that’s to much of a lump-sum. Or put it all in and do some tax-loss harvesting if the market goes against you…

Maybe I missed it, but does this simulation assume maintaining the nest egg at the end of the 60 years?

I assumed a 50-year horizon and 0 final asset target, though, in practice you will likely not spend down this big a nest egg unless returns are really, really bad.

Impressive work.

I’m confused by the 5.88% RMD in this statement: “At age 70, the minimum required distribution is 5.88% (=1 divided by a life expectancy of 17 years, according to the IRS tables), so that’s a whopping $300k+ in annual and taxable withdrawals from the 401k starting in 2041/42.”

In my online research, I keep seeing 3.65% as the first-year RMD, followed by 3.77% in year 2, 3.91 in year 3, 4.05% in year 4, etc. I believe these were calculated from the Uniform Life Table (Table III at bottom of https://www.irs.gov/publications/p590b index.html#en_US_2014_publink1000231236)

Which year 1 RMD figure (5.88% or 3.65%) is correct, please?

Thanks!

You are correct. Thanks for pointing this out. The table for married couples with age difference less than 10 years is Table III. 27.4 years life expectancy means 3.65% RMD.

This implies ~$190k in forced RMD and it would push the taxable income “only” into the 25% bracket in combination with the other income (SocSec+Pension). Still quite painful, so it doesn’t change the gyst of the whole story!

Thanks for the pointer!!!

Thanks for the clarification/correction, ERN!

What tools would you recommend using when deciding how much money to convert to a Roth per year? It’s easy to imagine a similar situation (perhaps with fewer years to convert) where converting some money in the 25% bracket would be correct.

I currently don’t use any tool. The one main measure to compare is the look at the (likely) marginal tax while converting and the marginal tax in retirement. If the tax in retirement is higher then convert.

There is another twist, though, and that has to deal with the potential issue of generating additional taxes to pay for the conversion now. Say, you have to liquidate assets with capital gains and pay capital gains taxes simply to raise the cash. That additional tax burden has to be factored into the marginal tax rate today.

Cheers! 🙂

Thanks. I’ve been looking at the Retiree Model Portfolio Spreadsheet from BigFoot48 at Bogleheads.org (https://www.bogleheads.org/wiki/Retiree_Portfolio_Model) and Optimal Retirement Planner (i-ORP.com) to validate my intuition (which is similar to yours) and wanted to make sure that I wasn’t missing a better tool.

The main reason that I’m not confident is that tax brackets when RMDs start can vary a fair bit depending on investment returns in the interim. Still, a weighted average portfolio balance at age 70.5 based on Monte Carlo simulations, or a calculation using a ballpark assumed fixed return (like the 6% that you used for Captain Ron) are likely to point in the right direction, and as long as the current tax bracket is lower, there’s some slack built into the calculation.

True, there is uncertainty about future brackets. a) from politics and b) from returns. I am a little less worried about b) because when returns are stellar I might increase my withdrawals and if returns are bad I will decrease them.

Enjoyed reading this ERN and RON. The Roth strategy is particularly interesting to convert more now to mitigate issues later. We will also have a first world RMD problem but not quite to the extent of Ron’s large tax deferred account.

Curious about essential baseline living expenses for Ron and his wife, including insurances for boat and healthcare and boat maintenance. I imagine it is much lower than a full home but fascinated to see how much surplus they will have for fun stuff!

Happy sailing and great case study!

That’s a great idea! Even being a complete landlubber myself I would be curious to see what the budget looks like for this exciting lifestyle. Maybe Capt’s Ron wants to start his own blog. Or post a guest post here on the ERN blog to share his experience!

ERN,

I’d totally be willing to do a guest post. Perhaps after the first year of retirement as a follow-up. Not sure what people would be interested in but some potential topics could include our actual expenses, any financial surprises, a peak into boat life, the withdrawal strategy implemented, and anything else of interest.

Absolutely! Consider this an open invitation. Looking forward to that!

Mr. Pie –

I’ve been told that the cost of sailing is like the cost of life on land. You spend what you have. We plan to set a budget and live below it, much like we have for our entire life on land.

Sailing will be a completely new adventure for us so we’re not exactly sure yet about most costs. Boat insurance is already arranged and that is $2,300 (usually about 1.5% of boat value). I’ve read that we can expect about $14,000 (10%) for boat maintenance but that’s highly influenced by how much work you hire out. I hope to lower that cost by doing most work myself. Medical insurance is another mystery that we’ll soon unravel. At this time we’re thinking we’ll get a catastrophic travel plan but if we want to go for full insurance I think we can and have $15k budgeted for that.

The expenses while living on the boat can fluctuate wildly. We plan to anchor out most nights, which is free. Marina stays are great for the convenient access to shore but we’ll not be doing this every night as costs are $75-$200 per night. This cost varies and is charged by the foot (we have a 37 foot sailboat).

I hope my rambling helps.

I’m curious to see how this strategy held up in the last few years. Will you be able to provide an update? I am interested because this is something I plan to leverage for my own retirement down the road (15-20 years from now). The volatility in the last 3 years is why I am curious in seeing how the portfolio did. Thanks!

The portfolio is doing really well thanks to a variety of factors…

– we sold our house and kept $250k cash from the equity as spending money, while investing the other $300k.

– we averaged $80k annual spending our first 5 years which is far less than Big ERN projected was safe. (Avg 2.25% withdrawal rate)

– the lower spend and cash from house has meant no equity sales were needed to fund our retirement until this year (year 6). Our $80k was sourced from dividends ($30k) and house equity ($50k)

– we’ve converted about $70k each year from Traditional to Roth.

I did provide an update to our lives and Big ERN published it in May 2019.