The other day I was browsing on Amazon to look for the book “The Simple Path to Running a Pension Fund” and couldn’t find anything. Maybe Jim Collins is working on that right now? Or Mr. Money Mustache might have a blog post on the “simple math” or wait, I mean the “shockingly simple math” of running a pension fund? Duh’uh! Of course, there is no such simple path/simple math! Because it’s no simple task. Lots of people are involved in running a pension fund. And we’re not just talking about the operational people; customer service reps, lawyers, etc. There would also be a bunch of highly-trained investment professionals taking care of the portfolio. When I worked in the asset management industry I talked to them frequently because a lot of our clients were indeed pension funds.

And I realize that – strictly speaking – I’m actually running a pension fund right now. For a married couple like us, it has only two beneficiaries, my wife and myself. I could count our daughter as beneficiary #3 because she’ll get some money for the first two decades or her life, but strictly speaking, she’s more of a “residual claimant” who’s going to get most of the “leftovers” when Mrs. ERN and I are gone. All of us in the FIRE community are running our own little one-person or two-person pension funds. And of course, in a lot of ways, running these small-potato pension funds is a lot easier than what the big guys (and gals) are doing. We don’t need fancy buildings, lawyers, customer reps, etc. But that’s the bureaucracy side. How about the mathematical and financial aspects? I’ve obviously written about how decumulating assets in retirement is clearly more complicated than accumulating assets while working (see Part 27 of this series – Why is Retirement Harder than Saving for Retirement?) but I was surprised how my DIY pension fund faces math/finance challenges greater than even a large pension fund. So, here are seven reasons why I think my personal pension fund is a heck of a lot more challenging than a corporate or public pension fund…

1: The “Law of Large Numbers” won’t work for us

In other words, we face much more longevity risk! What do I mean by that? A pension fund with thousands of beneficiaries can rely on actuarial calculations and thus make reasonable assumptions on how many people die along the way and how that will reduce future expected liabilities. It sounds very morbid but it is actually perfectly legal and even the proper and prudent thing to do.

Let’s look at an example. Imagine a pension fund has 1,000 retirees, all 65 years old males, then we can plot how many of them will still be alive over the next 5, 10, 15, etc. years. That’s what I do in the chart below. The blue line is the share of 65-year-old males still alive at the ages plotted on the x-axis. For example, not even half of the original group makes it to age 85, according to the survival tables from the Social Security Administration. And the pension fund will have to put aside less money because of that. (side note: this is just for illustration. An actual pension fun will undertake much more sophisticated calculations taking into account more demographic characteristics, survivor benefits, etc.) A DIY pension fund doesn’t have that luxury. What most retirees will do is to assume a “reasonable” life expectancy of, say, 95 years that you don’t outlive with a high enough probability (hopefully higher than 90%) and then plan for that 30-year retirement. So, the DIY pension fund would have to plan for larger payments, see that green area, to hedge the one-person longevity risk! For full disclosure, there’s also that small red area that the pension fund has to cover past age 95, but it’s so much smaller and also so far in the future that it’s likely negligible.

In any case, how much of a difference does that make, mathematically speaking in a safe withdrawal analysis? A huge difference! I ran some safe withdrawal simulations and looked at the two different scenarios: 1) a DIY pension fund, i.e., a 30-year retirement horizon with level withdrawals and 2) a pension fund that takes into account the conditional survival probabilities of a large number of participants and where the expected payments decline due to participants passing away.

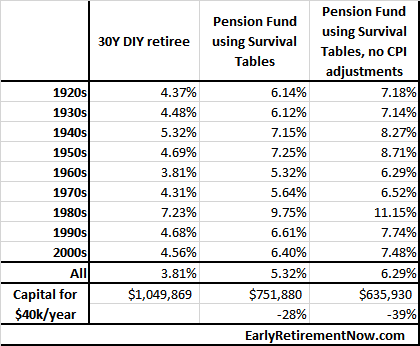

For the results, please see the table below:

- The fail-safe initial withdrawal rate would be 3.81% for a 30-year retirement horizon with level withdrawals over that period. The worst-case scenario that pushes the SWR below 4% occurs during the mid-1960s where you have lackluster investment results for a number of years before the sequence of recessions hit in the 1970s and 1980s.

- In order to fund a $40,000 a year retirement budget, we’d need just under $1,050,000 (=40k/0.0381) to guarantee not running out of money in the historical simulations

- A pension fund using the actuarial assumptions of average 65-year olds could offer 5.32% initial withdrawals to all living participants. But over time, as participants die, the outflows will trend lower according to the Social Security survival table.

- In order to fund a $40,000 benefit to the surviving participants, the pension fund would need only about $752,000 per participant. A full 28% less than the DIY retiree! That’s because the real pension fund can average out the longevity risk among all participants.

So, in other words, a real pension fund with a large number of participants can offer a much higher fail-safe benefit than our DIY retiree. Conditional on surviving, a participant receives over $53k a year, while the DIY retiree planning on a 30-year horizon can withdraw only about $38k per year (with COLA) for 30 years to guarantee not running out of money in the worst historical episode. The pension plan would pay out slightly more initially, but then after about 12 years start paying less overall (though still paying $53k per survivor) to make up for that. See the cash flow chart below.

Also, just in case people are interested, here’s how that same picture looks like for a 45-year-old male retiree, i.e., my age. The decline in expected survivors is clearly more gradual because the initial death probabilities are smaller (phew!!!) but you can still see that large green area of “wasted” resources that a DIY pension fund needs to set aside relative to a “real” pension fund.

2: A pension fund’s payouts are (more) predictable

The pension fund has to pay what it promised to pay to the surviving beneficiaries according to some pretty explicit benefit formula. If a beneficiary can’t make ends meet in retirement with that benefit, that’s the beneficiary’s problem. Not so in my DIY pension fund. We also have tons of additional uncertainties: paying for little Ms. ERN’s college, maybe graduate school, and also our future health expenses, nursing home expenses, etc. In fact, some of the most frequent concerns and questions from readers are related to exactly this issue: people are worried about the uncertainty of health expenditures, long-term care, nursing home costs, etc. Not just the expected values but also the great uncertainty about their personal idiosyncratic expenses. In contrast to a regular pension fund, your personal DIY pension fund faces all those risks in addition to the portfolio risk!

3: A corporation running a pension fund is a “going concern” and finds it much easier to deal with future shortfalls

Before retiring in 2018, I worked for a corporation with roots going back over 200 years (!) to a bank founded by Alexander Hamilton! It also has a pension fund. Though it’s been phased out over time, I’m still eligible for a small pension when I turn 55. If that pension fund ever were to get into financial trouble, sure, the CFO would be bitching and moaning but as long as the corporation is run profitably it can and will be done. That’s a lot harder for a DIY pension fund like myself. Humans, in stark contrast to corporations, have a limited “shelf life.” It’s a lot harder for a 70-year-old retiree to replenish his or her pension fund than a 70-year-old or even 200-year-old corporation.

Of course, the mantra in the FI/FIRE community is that the solution to Sequence Risk is to just be flexible. True, I could probably get my foot in the door in my old industry again (finance/asset management) if I wanted or had to. In the next year or two! But I have no illusion that the prospect of getting a job as lucrative as my old one will dwindle over time. And that’s just the way things are: both due to our advancing age and the growing gap in our resume we’ll have a harder and harder time supplementing our DIY pension fund in the future. It may not even be hard in absolute terms – I guess I could become a greeter at Walmart – but it certainly is in relative terms; relative to my earnings potential pre-retirement. That’s in stark contrast to a corporation which will hopefully stay profitable no matter how long it’s been running. Of course, even a corporation might get into economic trouble and may even go bankrupt. But the expected rate of decline in earnings potential for a large established corporation is certainly less than for a human.

4: We face more asymmetric risk than a pension fund

Let’s face it, chances are we vastly over-accumulated assets. In other words, by the time my wife and I are gone, we’ll still have a sizable nest egg. Of course, the money isn’t wasted because our daughter will get it eventually but, still, this means that we obviously worked too long. How long is anybody’s guess but I figure I could have retired at least one year before our actual retirement date in 2018. Will I beat up myself over this? Certainly not. It’s the rational thing to do because we face a very asymmetric risk: Running out of money in retirement is a lot more catastrophic than working a year longer than I have to (unless, of course, you work in a really, really horrible work environment!!!). And in light of this kind of asymmetric risk, it’s rational to err on the side of caution. There are many examples where you do so:

- I’d rather arrive 30 minutes before my plane’s departure than 5 seconds after the gate closes. Think of all the time I’ve wasted waiting for my flight! But missing a flight is enough of a hassle, so I’m willing to pay that price.

- Imagine you prepaid your rental car’s gas. The optimal thing to do is to return the rental car with the tank completely empty. But who does that? I’d rather leave a gallon reserve in the tank before risking running out of gas one mile before the rental car agency. (and I’d miss my flight in that case, too, oh my!)

- Any kind of insurance: auto, life, liability, etc.. Or running extensive medical tests to rule out serious diseases, etc.

And any time we err on the side of caution there is this inefficiency of wasted resources. Wasted hours at the airport, wasted gas in the rental car and “wasted” money in our nest egg. A pension fund, on the other hand, has a much more balanced risk profile. The money to fund the pension plan comes from the cash flow of this going concern. It’s just a matter of when. If the pension fund is overfunded now it means that at a past date too much money was diverted from operations to the pension fund. Thus, a slightly underfunded pension plan isn’t as scary as a DIY retiree with an underwater portfolio! Which brings us to the next point…

5: A mildly underfunded pension plan might even be optimal!

Going back to the previous point, I suspect that for a corporation, not only are the risks roughly balanced. There may even be a rationale for a corporation to keep its pension plan slightly underfunded. An overfunded pension plan means that precious resources have been taken away from operating a (hopefully!) profitable business enterprise. Just to give you some numbers here: Most corporations I looked at have ROEs (return on equity) in the high single digits, even 10+%. Some of the tech companies even 20% and more, although I doubt that many of them have pension funds. Why would you divert money away from such profitable ventures and into a pension fund that’s likely very bond-heavy with returns in the low single-digits? Of course, a corporation can’t take this too far. It can’t be severely underfunded or even get rid of the pension fund portfolio altogether and promise to pay benefits from future profits. That would run afoul with the regulators. But within bounds, it indeed seems optimal to be slightly underfunded.

But for us DIY retirees, living years or even decades with an underfunded plan might not be so ideal. It doesn’t make for a very relaxing early retirement if your personal pension fund is underwater and you have to think about that Damoclean sword or retirement ruin when you’re supposed to enjoy your retirement! I enjoy my stress-free retirement knowing that we have multiple layers of safety margins! Another dimension where my DIY pension fund seems a lot more challenging!

6: Most corporate pension funds don’t offer inflation adjustments

If you have a government pension with COLA (cost of living adjustments) count yourself lucky. Most corporate pension plans don’t. So, how much of a difference does it make if a (corporate) pension fund gets to skip the CPI adjustments? Even though this is a simple question, there is no simple answer to this one. I would normally assume a “reasonable” inflation estimate going forward, say, 2% per year, and see how a portfolio would have performed in the historical simulations if we had shrunk the real withdrawals by this 2% figure every year (even though inflation has been been very different from 2% for most of U.S. economic history!!!). So, let’s do that in the context of our little pension fund example above. Let’s look at the fail-safe withdrawal rates if we assume the pension fund can also shrink real benefits by 2% per year, see the table below:

- Say hello to the 6% Safe Withdrawal Rate! Even in the tumultuous 1960s-1980s, a pension fund could have offered a fail-safe withdrawal rate that’s way out of reach of a DIY retiree like myself: More than 6% in the 1960s and more than 7% at the stock market peak before the Great Depression.

- Actually, the true historical SWRs would have been even greater because realized inflation was a heck of a lot bigger than 2% during the tumultuous 1970s and 1980s (going to double-digits in the worst years).

- So, to fund a $40,000 retirement benefit per beneficiary, the actual pension fund could reduce the portfolio size per beneficiary even further, to about $636,000, and still be confident that this would have survived even during the tumultuous past recessions. That’s 39% less than the DIY retiree!

7: Keeping up with the Joneses? Not a problem for a pension fund!

One other issue has been on my mind and this has been brought up by readers quite frequently as well: should our retirement budget increase faster than CPI inflation? You see, real GDP grows at a positive rate and that’s true even when accounting for population growth, i.e., calculating the per-capita real GDP numbers. Specifically, between 1950 and 2017, real per-capita GDP grew by about 2% annually (real GDP by about 3%, and the population growth was about 1%, so the ratio of the two grew by about 2%), see the chart below:

Do you see a problem if you adjust “only” for inflation? Over the years and decades, we will fall behind more and more relative to the average U.S. consumer. Sure, I can still afford my consumption basket from 2018 in the year 2048. But what if everyone around me has consumption budgets that grow at 2% above inflation and they can buy all those fancier gadgets? In 2048, will I feel like someone stuck in the 80s today? Maybe if you’re a traditional retiree you don’t care so much about falling behind with your gadget portfolio when you reach your 80s and 90s. But we retired at ages 44 (Mr.) and 35 (Mrs. ERN) and have many more decades to participate in the advancement of technology.

So, I simulated how different withdrawal patterns would have worked out in the historical simulations. Specifically, I ran my Google Sheet with six different assumptions:

- 2 different retirement horizons: 30 years and 60 years, i.e., traditional vs. (very) early retirement.

- For each, I look at 3 different spending patterns: “only” CPI adjustments, CPI+1% additional real growth and CPI+2% growth

- Throughout I assume a 60/40 Stock/Bond portfolio and zero final net worth target.

Let’s look a the results, see the table below. Growing your withdrawals to keep up with what your average fellow Americans’ consumption budget will dramatically reduce the safe withdrawal rates, or, equivalently, dramatically increase the required capital to fund a specific initial spending target. Just a 1% increase over the CPI requires a 13% and 18% larger nest egg for the 30 and 60-year horizon, respectively. With a 2% increase, we now push the fail-safe withdrawal rates to just under 3% over a 30-year horizon and into the low-2% range over a 60-year horizon.

Side note: the same results also apply if you assume that your personal inflation rate the posted CPI figures by 1% or 2%, also a frequent inquiry by readers. A lot of retirees are worried that their own personal inflation rate will be much higher than the average posted CPI rate when we age. You don’t even have to employ any kind of conspiracy theory (the evil government underreports CPI to lower the COLA of pensions and Social Security); older folks consume more on health care & nursing home care (traditionally high inflation rates) and less on tech gizmos (low, and even negative inflation rates).

So, in any case, maybe I’m worried for no good reason and our expenses for a healthy and comfortable retirement grow just in line with the CPI or less. But the fact that I think about this and the fact that readers have brought this up several times means I can’t ignore this issue. It’s something that a regular pension fund that offers COLA (most public funds) or no COLA at all (most corporate funds) wouldn’t have to worry about. The risk of future spending growth rates is completely outsourced to the beneficiaries!

Conclusion

Withdrawing money is harder than accumulating money, just from the mathematical and financial point of view. But I was surprised that my personal withdrawal math problem is even a bit more complicated than that of a real-world pension fund:

Accumulating Money < Pension Fund < DIY Pension Fund

The best defense against retirement uncertainty? Educate yourself! Make sure you check out the other parts of the SWR Series: a list of all parts and a summary and guide to first-time readers is available here on my new “landing page” of the SWR Series! Or anywhere else on the web! It’s harder than many people think but still easy enough that anyone can do it!

So not only were pensions “better” they are “cheaper.” So why get rid of them again?

Because getting rid of a pension and moving employees to a 401k shifts the risk to the employee and saves the corporation money.

That too! But note also my comment: the risk on the employee worked out really great for a lot of cohorts in the past! 🙂

Good point. Remember that a pension is better in the worst-case scenario. In the better than worst case scenario, you’ll reap great benefits from a DIY approach. So, quite a few folks have done much better personally with their 401k/IRA/etc. and will leave tremendous wealth to their kids.

Hi Big Ern,

Excellent article , I totally agree with you on the asymmetric risk and the impact of missing your flight vs coming too early and waste time on the airport.

Personally I don’t consider leaving inheritance as a waste, it is very likely to benefit your children if they are disciplined and

educated about Money management. You may opt for charity donation if you don’t want to leave any inheritance. I think

it is good problem to have considering the cost of working one more year.

Congratulation on the nomination, I am rooting for you to win .. I really enjoy your analytical style of writing. 🙂

Very good point. I meant to use the word waste mostly in quotation marks. That money is not wasted at all in most cases. 🙂

Great post. I’d add one other: pension funds don’t face SoR risk since they allow you to diversify returns over time (worker cohorts).

Very true. They look like they face SoRR on one single cohort. But they can also shift that risk across the different age groups. Very valid point.

Should have made that #8. 🙂

You are absolutely wrong. Pensions face great SoR risk, especially if they are an older plan with declining labor participation and increasing benefit distributions. To keep it short here since the liabilities are discounted at a fixed (and often wrong but always non-volatile) rate and the funding of those liabilities are with increasingly volatile assets pension funds have large exposure to a asset/liability mis-match (SoRR). In fact this is what is plaguing many DB plans now, especially since the asset side of the balance sheet had overly optimistic return assumptions. The best way to not have SoRR exposure is to follow a strict ALM (asset/liabililty matching) approach which requires matching new annual liabilities with low (or with zero-coupon bonds no) volatility assets. Sadly this meaningfully lowers the rate of return expectations but it greatly increases the probability of success and also greatly reduces the SoRR exposure. For further education you can read the fantastic books by Ronald J. Ryan or Barton Warring. Both are exiclent and essential to understanding the nature of this problem.

The only way to not

We may have different definitions of what SoR risk is. I am using it as an asset based concept, meaning the presence of net distributions/contributions creates a different cumulative balance depending on the order (not the magnitude or volatility) of returns. Liabilities don’t renter into it. I believe this is the common definition of SoR risk.

That said I agree that there is lots of ALM risk in pension plans apart from any SoR risk.

And plans with large net distributions such as frozen plans do face SoR risk (see comment in response to Actuary on Fire).

Agreed on definition and I am deeply involved with DB pension issues. SO to be more specific the problem is that DB plans rely on a long-term RoR to keep things in balance but as we know those returns are never level. Since DDB plans are under distribution they,can and actually have gotten into trouble when they are hit with those early bad return years. I have direct experience with one of those now where the plan was 125% funded in 1999 and is now filing for a MEPRA reduction. It quire literally is the same thing. Finally, I am unaware of any DB plans that are practicing pure ALM as prescribed by Ryan and Warring etc etc. Any plan not totally defeating liabilities has SoRR exposure, it’s just a matter of degree. SoRR is a result of being a fund under distribution.

I’m thinking perhaps the author of this article shouldn’t have retired at 44. Nothing in life is guaranteed, including a comfortable retirement. I’m still trying to get my inheritance from my “trustee” brother who has owed this to me for twelve years!! In the meantime, I lost my home to foreclosure which was what the money was for. Being single and female didn’t help either, nor did the 2008 real estate devaluation of my home.

I’ll take my chances with the market, thank you so much. At least market risk is something that can be understood from a statistical point of view. Not so sure how to model legal risk, like enforcing a payment from a trustee.

Very good points! A plan without any or only little new inflows definitely faces SoRR.

And true: fully funded plans should look into the ALM. Unfortunately, the reality is that most plans are underfunded and are forced to juice up their returns with riskier assets! 🙂

Except when bonds have negative rates. Then you’re screwed because you tied the pension managers’ hands to bonds.

Yet another relevant and wonderfully crafted analysis and article for me Prof. ERN since I retired in 2018 at the age of 58 with no pension plan but my meager monthly Army 10% disability money which is only presently $140 month which I jokingly tell everyone is my beer stipend. I am seemingly surrounded by friends and family members who have or will have a good pension plan. I have to explain to them that I am managing my pension of one after many years of maxing out 401Ks, 403Bs, & IRAs how critical it is for me to do it right. Sites like yours helps me tremendously. No wonder why you have several nominations. Congrats.

Thanks for the feedback, Eduardo! And thanks for your service in the military! Very much appreciated!

I’ll also get a small pension at age 55 and that will also be my play/beer money. 🙂

Good summary, as usual. In your next post in the series, are there specific actions that you recommend that we, as managers of our pension fund of one (or two), should be taking, based on best practices of actual pension funds, to reduce risk, volatility, etc. I am less about increasing alpha and much more about reducing volatility / risk whenever possible.

Thanks! Well, I’ve written about ways to alleviate risk (glidpepaths: parts 19. 20. Flexibility: part 18).

The problem is that volatility reduction will also result lower expected returns and higher long-term risk. So, we just have to live with the short-term vol and then a) use a lower initial WR or b) be prapared to cut your withdrawals (flexibility).

I plan to also write a post on annuities at some point. That’s been requested as a risk-reduction tool by many readers.

Interesting analysis! The significant gap in required funding between DIY vs actual pension funds makes sense, however I’m struggling to reconcile this with the general unpopularity of pension funds amongst the FIRE crowd. Are pension funds taking such a huge slice of the pie in profits which results in them being so unappealing? Or do you think the downside of no inheritance is enough to explain the gap? If more the former it seems like there is a potential opportunity for FIRE folks to band together to create a more efficient fund. Interested in your thoughts!

We have to distinguish between pension funds and annuities.

Annuities indeed have extremely high fees. They are not very popular in the FIRE world! Shooping around is paramount! If you find a low-cost option it can potentially be good supplement to your FIRE plan.

Most pension funds do a pretty good job at keeping expenses low. But it’s a case-by-case analysis. If you have the optioin of a pension vs. lump-sum payment it takes some analysis to figure out what’s better.

I wondered the same thing. Recall how many of the labor unions and fraternal orders that came out of the late 1800’s – early 1900’s focused on providing burial insurance, life insurance, or a “community chest” of sorts to help their members and families in the event of economic setback.

Seems like early retirees who did not want to leave a big inheritance could band together in the same way, retire on higher SWRs, and save years of their lives from cubicle doom. Annuities and insurance supposedly fulfill that role today, but the ROI is ridiculously low because these companies must extract their own profits. A group of investors could form their own fund with a clause that one’s stake in the fund is absorbed by the others upon death (easy enough to do through contracts and wills). This would mitigate SORR for whomever lived longest.

Excellent point! I was wondering about the same. Maybe have a FIRE pension/annuity fund? It will likely never come to pass due to regulations but it’s an interesting idea in theory! 🙂

This is a fantastic post. As I turn 60 this week, it makes me wonder whether my husband and I would benefit from an immediate annuity, rather than going it “alone”. Using an online annuity calculator, if we get a joint annuity for 1 Million dollars, with both of us age 60, the payout is $47256 annually. Since this is both more than your typical $40,000 per year for 30 years (of course not in YOUR book, ha ha), and will take us longer potentially than 30 years if we are lucky enough to live a long life, isn’t this a good deal? In our case, we don’t have heirs, but of course it would be nice to leave something behind. It really gets me thinking.

Also, I notice the part of your post about corporations under-funding their pensions, but making it up in future profitability. The state of California, shown in your lovely photo, is under-funded. And they are SO “profitable” that it is no problem, huh?

Susan,

I don’t believe your 47256 has a COLA adjustment. You will lose out to inflation.

Vic

Hi Susan! Thanks for stopping by!

For a joint survivorship that’s probably a pretty decent annuitiy yield. Sure, it’s 4.7% NOMINAL (as others have already pointed out) and thus is eroded away by inflation. But if you take the bond portion of your, say, $1m portfolio ($400k) and transform that into an annuity and keep the remaining $600k in stocks it may not be such a bad compromise. I’d never go “all in” with the annuity, of coure.

Also, I didn’t mention this about the public pensino funds because I don’t want to get into politics. But since you bring it up: of course, public funds want to be underfunded as well. Public spending is also more “profitable” than funding a pension fund. Politicians care about spending now, not properly funding the pension fund. Let future politicans deal with the mess. 🙂

Thanks for another great entry in one of my favorite series. I hadn’t really considered managing personal retirement as equivalent to a pension, but it makes perfect sense. You make managing a large pension sound so manageable, but the public perception is they are disasters for corporations and government. Of course, it’s all about who bears the ultimate risk/reward. Some government pensions are built on unsustainable assumptions.

I stand to benefit from a public pension at 55, but it’s difficult to determine the potential value given potential changes. My current strategy is to plan absent of the pension, and then factor it in as the time horizon narrows. This means I’ll most likely work a bit longer than needed – as you said caution creates inefficiencies. Fortunately, I mostly enjoy my job so I can accept this for now and take on more risk if that changes.

Best of luck on the Plutus Award – you definitely got my original nomination and new vote.

Thanks!

Yeah, that’s a great uncertainty about what will happen to a pension down the road. If I were you, I’d get an estimate and apply a 20-30% “haircut”(reduction) to deal with the uncertainty. But still apply it in the Google Sheet as a supplemental cash flow. It can make a huge difference in the SWR!

This is very sage advice. My pension fund ($2B assets and I am 60 Y.O.) is applying for MEPRA suspension and the best guess at this point is 23%. we were 123% funded in 1999!

Oh, my! Best of luck with that one! Thanks for sharing!

Not sure i agree with the point above that sequence of returns impact is less for a pension fund than an individual. Any pool of assets that is being drawn-down (or even being contributed to) experiences sequence of returns.

Since a pension fund has no control over the timing or amounts of the cashflows, unlike an individual who can tighten his belt if markets get rough, then I might guess SORR is higher for a pension fund.

The way I think about pension funds is that it’s like being a single investor who knows precisely the day you will die. Since for a pension fund you have the pooling of risks and law of large numbers that you mention, you are essentially reserving to the population mean life expectancy. I’m sure safe withdrawal rates would be a lot more relaxed if you knew the precise date of your death!

A healthy, going concern pension plan will have both contributions and distributions. Case in point, Calpers last year paid benefits of roughly 7.4% and received contributions from employers and members of 7.8% of assets. Negligible SoR risk. A frozen plan with no new worker cohorts will run off and be subject to SoR risk. Off course, if it gets too bad the plan sponsor has to make additional contributions (note that on the contribution side there is indeed control over timing and amounts of cash flows.)

Very well said! 🙂

Sorry, this is a faulty way of looking at this. The 7.4% new contributions were also the creation of new liabilities. So while the new cash flows can and do have an ameliorative effect on SoRR at that time, the relationship between the discount rate of the liabilities and the RoR assumptions needs to be correct. It the RoR experience is less-than-expected the SoRR from reaper is waiting in the wings.

As long as the payments to young workers are years/decades away, there is indeed less SoRR. True, they also add to the liabilities, so there is Return Risk. But no SEQUENCE of return risk.

True. If this is a mature pension fund with only retirees and no new workers contributing (which is the case in many corporate plans now) then this plan is exposed to Sequence Risk like everyone else.

Though, if there are indeed young workers contributing, that would cushion the Sequence Risk.

Cushion, yes a bit. Alleviate, no. Any structure with cash inflows, invested assets, current and discounted future liabilities (cash outflows) has innate SoRR exposure. The best way to to lean in two defeating liabilities as they are accrued but few DB plans do this anymore as they have embraced great risk asset returns to do more of the ‘heavy lifting’.

Again, as I mentioned in the other comment: Don’t mix up average return risk and sequence of return risk.

I truly do mean to say SoRR as it it that mechanism which can (and indeed has) led some pension funds to develop chronic negative cash flows and get pulled into a death spiral. You are correct that achieving less-than-planned-for average returns is not necessarily an issue (to a degree) though. There are a number of plans in RZCD that have realized the manifestation of SoRR teacher to the double whammy of 2000 and 2008.

Yeah, we’re not disagreeing on this. Absolutely, some PFs were hit by SoRR and are underfunded for the exact same reason SoRR wreaks havoc on invidiual retirees’ portfolios.

AOF is correct. SoRR exposure is not meaningfully less for pension funds. While they gain in pooled-risk they lose in flexibility to modulate outflows.

This is a fascinating post. Thanks again for making me think about retirement from a different angle.

The large numbers advantage you mentioned above makes me wonder if that is not a case for considering Annuities too for retirement. I understand these are products that have a somewhat sketchy reputation in the FI community, considering their complexity, fees etc. But when I think about the large numbers advantage, wouldn’t that apply to an annuity too where the insurance company is weighing the risk based on the average of all participants rather than a single individual? Wade Pfau seems to advocate this approach in some of his work. Would be really interested in hearing your opinion on this. Is there a place for an annuity in FI retirement planning?

Annuities are on my to-do list for the SWR Series!

If you shop around and find a low-fee annuity it’s certainly something to consider. But I’d use only a portion of my money to do so. 🙂

And I would try to wait for higher interest rate environment.

Susan, above says how about an annuity. But Vic points out that the $47,276 Annually from the annuity is not inflation adjusted so not a better outcome. However, consider what happens if you put, say 3/4 of your bond allocation into an annuity. This would almost certainly produce a better return than a bond ladder, and you would still have all your stocks for growth and inflation protection. I have done this.

Excelent point! Use anunities only for the bond portion. A bond ladder is still OK if you try to hedge only the first 10 or so years (most impact fro Sequence Risk), though…

You speak my lingo, but it’s even more convoluted. Your personal pension fund relies on that +GDP but also is taxed. Your personal pension fund is leveraged. If you “4 x 25” for 30 years for example, you are playing the odds that some return on the “25” will pay for 5 more years. That’s called leverage.

You talk about people dropping out at death, this risk also exists in the personal DIY space. When you die your 9 years younger wife will lose 1 SS income and 1 tax deduction and be booted 1-2 x into a higher tax bracket, and with your sorry ass in the ground she will have to fend for herself with this added burden. It turns out if a woman reaches 65, she has a 30% chance of reaching 90 and a 2% chance of reaching 100, most likely in a nursing home.

In addition the risk of future health care can be moderately stratified. Each of you are going to die of something. I worked up some stats and 1/3 will get some kind of cancer in their life. It may be a trivial skin cancer or a serious illness. 20% of that 1 get serious illness. Of the 20%, 20% die which means 80% live. Of the 80% who live, 40% of them went 100% broke within 4 years after their illness. Imagine being 60 getting sick and being 100% broke at 64, 1 year before medicare and 3 years before FRA. It’s a dog food diet for you! Imagine you’re 65. 1/10 get Alzheimer at 65. The illness has a natural history of 12 years post diagnosis pretty much assuring some time in a 24/7 nursing facility. Survival could be much longer. The incidence of Alz at 85 is 1/3 so you might need care to 97. Men are dead by and large but women have a good chance of pulling the golden ring. If the husband spent all the damn money fighting cancer the wife is truly hosed. The idea therefore of “too much money” soon evaporates. You better pray God you have too much money. The widow maker may snuff you out quickly, there are worse things to contemplate.

There is another risk, boomer retirement aka demographics. Pension funds are NOT slightly underfunded but are missing about 1/3 of their need and require 7.15% return to keep up. A big old glut of boomers will accelerate that fund depletion. In addition people retired spend less. They go out to the early bird special, don’t buy cars, don’t buy houses. They do spend more on health care true enough but that presumes they have more to spend. If you retire with 20K savings, you have 20K to pour into the healthcare hole not 600K. SS will suffer a 25% haircut in 2032 PERIOD. Congress will not act because the law is already written and millennials now outnumber boomers and they will want at least something when they retire and the 25% cut will put SS on a good footing for some decades. Boomers vote but so do Millennials. A slowed down economy due to demographics means a safe WR is also slowed down.

Your analysis is great as always. Having excess money and a safer WR is the only way to fly!

Thanks, Gasem! Great analysis! Thanks for the detailed numbers! That’s on my mind too. There is huge uncertainty about our expenses when old. Could go well and we just live healthy until we peacefully pass away when 90. In that case we’ll need less and less money. Or one of the not-so-tail-events you mentioned. Pretty scary, and that’s why we do our retirement plan very conservatively.

Social Security worries me a bit, too. Also, the cuts won’t be linear. I still believe that the median voter is old enough to watch after the old. So it’s more like everyone above 55 at that time will suffer less and the young get screwed.

Cheers! Always love reading your comments! 🙂

Great analysis and perspective as always.

The asymmetric benefit/risk section got me thinking about our healthcare system in the U.S., which is often held up to ridicule for being too expensive for not enough (collective) benefit.

The ability in the U.S. for many of us to go directly to specialists for tests/procedures without a gatekeeper means we can decide individually to spend more to rule out the possibility of increasingly remote illnesses, or to have medical procedures with a low probability of long-term benefit (e.g., a knee replacement in one’s 80s).

In Europe I’m often struck by what seems to be a greater prevalence of older people walking with canes than in the U.S., which is maybe driven by the cost/benefit hurdle of knee replacement being determined by the state versus the individual?

So, maybe your DIY pension versus collective pension framework works in other realms as well, such as healthcare. Thanks for making me think differently about things, which I always find enjoyable!

Very good point. I have experience in both the German and U.S. healthcare system. There is certainly health rationing going on in Germany. I prefer the U.S. system even though it’s more expensive!

Great Post. I have felt this way about the demise of Defined Benefit and how it requires each individual to have excess funds in case they live longer than average, but you spelled it out so eloquently.

I think our country had just 1-2 generations that were able to benefit from Defined Benefit, and sadly we are headed back to the vast majority of retirees not have sufficient funds to enjoy their golden years. Social Security mitigates this, but really just keeps a minimal roof and food for most.

The effects of all of this (which we are already seeing) are average retirement age going back up.

Yeah, I think we threw out the baby with the bathwater. I still prefer to have my own funds that I can manage and then bequest to our daughter. But I would have preferred to have a bit more in Defined Benefits when I get older. To hedge the essential expenses.

It is truly sad but if you read Roger Lowenstein’s book “While America Aged” you will see that the DB structures had little chance of surviving owing to many influences having nothing to do with the actual funds’ purpose. The politics of budgeting, making promises and corporate earnings to name a few have played larger roles in the behavior of pension funds than the needs of the retirement commitments. SAd.

Great Post. Always interesting to compare: historically and then with individual vs. corporate DB.

Thanks! 🙂

Great Post….I also work for the Alexander Hamilton bank and qualified for the pension. I am a much bigger fan of the new compensation model that puts 2% of your pay in the 401k each year in lieu of the pension. Did you end up keeping the Mellon Cap (0 management fee index funds) after you retired? The bank does seem to be aggressively shoring up long term profitability, so the pension feels safe. Great post and gives me something to think about.

ERN,

Always love your stuff. Here are a few thoughts on your pension post, specifically the SE private plans. It’s worth pointing out that entirety of you comments #3 & #5 are only applicable to the SE universe which is smaller than those of the ME or public plans. Only the SE plan faces the choice of how much to invest in the sponsors equity or in external investments. And as regards that choice…

…….“Why would you divert money away form such profitable adventures?” The simple answer is because it is not the corporation’s money, it is a deferred component of the employee’s total compensation. It is not rightfully available for the sponsoring corporation to use in that way. Additionally, we have learned numerous times that layering the employee’s risk where they have a financial investment in the firm where they are employed increases their risk meaningfully. When a sponsoring corporation fails not only is the employee possibly out of a job they have last savings as well… and if the plan is underfunded they can lose there a third time. Finally, it has been some time since the majority of pension plans have been ‘bond heavy’ in their allocations. The fact is most SE, ME and public plans are equity-centric in their allocations and this includes alternative investments, Private equity etc. Most DB plan books look more like the book of a prop desk or hedge fund than A rightly sleepy conservative pension plan.

The “Why would you divert money away form such profitable adventures?”was a rhetorical question! I was very much aware that this is a) not legal and b) bad for diversification. 🙂

The irony is that when the DB went to DC they did exactly that: push people into holding company stocks instead of diversified index funds. 🙂

Sounds like you’ve just given everyone who has retired early a better answer to inevitable question:

“So, what do you do?”

“I manage a small family pension fund.”

Haha, that’s a good one. I shall try this one next time I get that question! 🙂

Have you considered using long expiration SPX puts to reduce sequence of return risk?

I tweaked your toolkit with a basic strategy. It isn’t complete as I hard coded the price of the puts as a percentage of SPX price. There has to be data out there we could use to calculate option prices for the entire series that would get us pretty close… If anyone knows where I can find it?

The strategy I used is pretty basic. For every quarter, if CAPE is > 20, buy a put large enough to protect 1/4 the equity investment, that expires 1 year out, with a strike price 10% below the current price. The put is held to expiration.

Obviously can’t draw too many conclusions without price data. However, the strategy does seem to help mitigate 1929 and helps to a lesser extent in 2000. It doesn’t help much for the long topping pattern in the late ’50s.

Below is my tweaked version of the toolkit. If you want to check my math, I added the two parameters on the front page for option price and strike price. In the “Stock/Bond Returns” tab, I added some columns at the end and modified column L.

https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1lqrzhvGIUig0YhPVhxwoQEjYVl1B12piqCm8jLesz34/edit?usp=sharing

Also, have you considered updating the toolkit to support leveraged strategies like the one you describe in your Synthetic ROTH IRA post (https://earlyretirementnow.com/2016/06/07/synthetic-roth-ira). I’d love to see more in depth analysis around how futures based leverage strategies affect SWR and risk in your models.

On a related note, have you seen the NTSX ETF that endeavors to track a 90% equity – 60% treasury portfolio. Any thoughts on it?

Wow, that’s great work! Ideally, put the “new” return series into the column for the “custom” returns. Then you can compare side-by-side the equity only vs. the equity+put protection.

Also, do you have more details on how you constructed that put series?

I like the leveraged strategies to add some bond beta. Right now, though, you have negative carry when the 10Y yield is below the 3M bill rate (maybe not for much longer). But in general it’s a strategy I really like. The expense ratio at 0.2% seems OK as well.

Have you considered modeling spending increases based on the National Average Wage Index instead of the CPI? If you want to keep up with the average consumer that spends 90% of their wages then that would be the index to use.

You could also do a hybrid rule – increase spending of the greater increase in the NAWI or CPI for each year/month of your modeling.

I think it would be a very interesting experiment!

No, because I don’t have a long enough series. The CPI is already partially relying on some back-filled data, so that’s all we can use. To gauge how much you have to adjust over and above CPI (probably around 1-2%) and use the COLA+1% and COLA+2% estimates as I did in the post.

Thank you for considering my proposal! 🙂

There’s a few more reasons why I feel looking at the wage index could be interesting. You’re right, it averages out to 1% above CPI, and MAX(AWI, CPI) averages out to 1.5% above CPI, however the deltas are quite significant in a given year, varying up to a 4-5% spread – like AWI of 1972 was 9.80% while the CPI was 3.30% – a 6.50% spread. The biggest reason for this is the AWI tends to lags one to five years of CPI increases. It takes time for employees to demand higher wages, move around (change jobs), and actually receive these wages, in response to realized inflation.

Since there is a lag time, I wonder if that could help some of the failure cases, or possibly change the SWR enough. Having a lag time of increasing spending, but still eventually maintaining purchasing power, could be helpful. The AWI also appears to give smoother increases throughout the 70s vs huge jumps of 11% inflation per year, for instance 1974 the AWI was a 5.94% increase while CPI was an 11.10% increase. Having a lag time of spending increases could also help significantly with sequence of returns risk in the early years of retirement. To normalize the AWI study to CPI you could do AWI – 1%, for a cohort that just wants to maintain purchasing power vs have real spending increases.

I’m not sure if you’ve looked at smoothing out inflation increases to a portfolio. From the initial looks it appears you haven’t yet. I think that would be an interesting article as well. I’m still getting caught up on all your extensive and excellent SWR articles! 🙂

You’re right about the data issues of AWI going back to 1951 and CPI going back to 1913. I’m not sure what are good sources of wage data to explore beforehand. The IRS for example has statistics of income for each year, say 1932:

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/32soirepar.pdf

They go back to 1916, while the CPI goes back to 1913:

https://www.irs.gov/pub/irs-soi/16-05intax.pdf

I hope my additional insights into the AWI are helpful and I hope you reconsider this idea for an article on modeling based on AWI or inflation smoothing. Cheers!

Thanks for the links. Yes, it would help if you don’t raise your spending quite as fast in the 1970s. It will also hurt you when you don’t lower your spending quite as fast during the deflation period in the 1930s. I suspect it’s a wash.