What? A new case study? I know, I had promised myself to wind down the Case Study Series I ran in 2017/18 after “only” 10 installments. It was a lot of work and a lot of back and forth via email. It takes forever! I mean F-O-R-E-V-E-R! But then again, there’s always a reason to make an exception to the rule! Jonathan and Brad from the ChooseFI Podcast had a very interesting guest on their show this week (episode 152). Becky talked about her experience of a late start in getting her and her husband’s finances in order. They started at around age 50 and became Financially Independent (FI) in their early 60s and retired a year ago. I should also mention that Becky recently started her own blog, appropriately labeled Started At 50, writing about her path to FI and RE so make sure you check that out, too.

In any case, Jonathan and Brad asked me to look at Becky’s numbers because I must be some sort of an expert on Safe Withdrawal Strategies in the FIRE community. I chatted with Jonathan and Brad about my case study results the other day and this conversation should come out as this week’s Friday Roundup episode. Because there’s only so much time we had on the podcast and I didn’t get to talk about everything I had prepared, I thought I should write up my notes and share them here. Heck, with all of that effort already spent, I might as well make a blog post out of it, right? That’s what we have on the menu for today…

Background

- Becky and Stephen (63 and 64 years old) live in Colorado and retired about a year ago.

- Their current nest egg is about $1,355,000 in financial assets.

- They also own a single-family home, mortgage-free, worth around $450,000 today.

- They are planning to live on around $80,000 after taxes, so they have pre-tax cash-flow needs of close to 90k per year. That would be a 6.6% initial withdrawal rate; sounds really high, but there are special circumstances that will make this withdrawal rate sustainable! More on that later!

- $60,000 of their budget is the non-discretionary base budget. $20k is for fun stuff and that figure can be reduced if necessary.

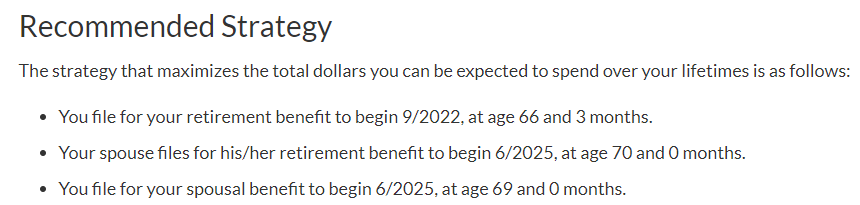

Social Security/Pensions: [Update 11/9/2019: I recalculated the Social Security timing with the help of “OpenSocialSecurity.com“]

Stephen had very high FICO/payroll taxable salaries throughout his life. He got pretty close to reaching 35 years of contributions at or close to the Social Security annual limit, so he expects $3,500 per month at age 70! Becky’s own benefits at roughly $1,000 are substantially lower than Stephen’s.

I found a great tool online: opensocialsecurity.com/ to determine the optimal Social Security timing. This is particularly useful in this case when you want to determine the timing of spousal benfits! The inputs: First Becky, who I assume was born in 1956, mid-year. Her own PIA (Primary Insurance Amount), i.e., the amount she’d get at full retirement age is $1,000:

Her husband is one year older and expects $2,680 PIA (which would translate into $3,500 at age 70!). You can also add the mortality table to reflect that they don’t smoke (I presume) and are generally very healthy (“Nonsmoker Super-preferred”)

And click “Submit” and the site spits out the recommended Social Security claiming schedule. Becky files for her own modest benefits in 2022. Then Stephen waits as long as possible, until age 70

The approximate benefits per month are (rounded to the closest 10):

- Becky on her own benefits: $990 in month 67 of the simulation (9/2022)

- Becky while on spousal benefits: $1,330 per month (11,933+4,080 annually). Basically, Becky’s benefits will be topped off to match half of Stephen’s PIA. Why this is not exactly equal to 1,340, I can’t tell.

- Stephen: $3,500 when reaching age 70.

Notice that the combined benefits amount to around $58k per year. That means, only six short years into retirement, they can reduce their withdrawals from the portfolio very substantially!

Other parameters/considerations:

- Around 17 years into retirement they like to scale down their budget by $10,000 p.a. due to less travel and just in general, living at a slower pace. I heard they currently drive vintage Porsches (yes, plural!) and when you reach your 80, it might be time to also literally slow down. Maybe switch to a Toyota Avalon?

- Around 21 years into retirement, account for the possibility that one spouse passes away. Social Security benefits are now “only” $3,500 per month (either Stephen’s benefits, or Becky getting survivor benefits). I assume the expenses stay the same, to be conservative. In reality, some expenses will go down but that’s also likely offset by a less advantageous tax landscape when the survivor has to file taxes as a single. So, my working assumption is always that when a spouse passes away the lower expenses and the higher taxes are a wash.

- Around 25 years into retirement, the surviving spouse will sell the house (value $450k in today’s dollars) and move into an assisted living community. This will raise the annual budget to $150k. Not quite Suze Orman territory but still a very generous budget!

- Becky wants the money to last until age 95-100 and still have $1,000,000 left as a cushion for health costs. I’d think that $150k a year covers a nursing home plus health costs pretty well, though, so I think that $1m figure is a bit of overkill.

- Becky and Stephen have kids and grandkids, but they haven’t explicitly factored in a major inheritance for their heirs. It sounds like they want to be generous while still alive, great idea!!! I also think there will be plenty of money left because a) the nursing home budget seems pretty generous and there is a high likelihood that you don’t live all the way to 98 or 100. So, with a large probability, there should be money left over for the kids/grandkids.

So, it looks like Becky and Stephen’s retirement will go through 3 major phases

- The first six years of very large withdrawals to fund expenses before Social Security kicks in,

- The next 19 years of living off Social Security with relatively small cash flow needs from the portfolio,

- The remaining years start with one large cash inflow. But then we also throw the regular budget out of the window and budget for a very generous $150,000 withdrawals in today’s dollars, which is more than 10% of today’s portfolio!!!

A few preliminary observations:

81.7% in a stock portfolio seems a bit high for retirees who plan not to work on the side. I will later recommend an allocation of 60% Stocks, 35% bonds, 5% Cash/Money Market, which is more appropriate to hedge against Sequence Risk. If you absolutely want to keep your 80+% stock share, it wouldn’t be too catastrophic either, but you’ll add some (unnecessary) risk! Remember, in retirement and in FI, you already won the game, why keep gambling?

Taxable bonds are in the taxable account. That’s inefficient! It crowds out your Roth conversions because the bond interest is ordinary income! Ideally, you hold taxable bonds in a tax-deferred account. Of course, people then wonder how can you withdraw bonds when you have 100% stocks in your taxable portfolio. It’s easy: money is fungible! Imagine you own only stocks in a taxable account and a Roth IRA with stocks and bonds. If you want to withdraw a certain amount from bonds without touching the Roth, simply take that amount from the taxable stock portfolio. But then in the Roth IRA move that same amount from bonds into stocks! Again, money is fungible!

So, I would suggest getting rid of all bonds in the taxable account (and buy bonds in the T-IRA and/or Roth to offset that). If that’s too intrusive for you, at least liquidate the taxable bonds first to finance the living expenses early on. And again: shift money from stocks into bonds in the retirement accounts to compensate!

Setting up the ERN Google Sheet

Let’s get our hands dirty! Here’s the link to the Google Sheet I prepared:

Becky and Stephen Google Sheet

As always, please save your own copy if you want to play around with the numbers. I cannot grant you permission to edit my official Google Sheet because I have to keep a clean copy for everyone! I won’t give you access to my brokerage accounts either! 🙂 To save your own copy, click File/Make a copy, see below!

Parameters in the main sheet:

- Allocation: Stocks 60%, Bonds 35%, Cash 5%. I played around with the asset allocation and the 60% stock allocation had the best-looking fail-safe properties. Sure, with 80+% stocks you will do much better on average, but you’ll also add some tail risk and the potential to run out of money 30 years into retirement!

- Horizon: 35 years = 420 months (Becky 98 years old or Stephen 99 years old)

- Final Value Target = 0% of initial capital. For now, I set this to 0 because I think that with the $150k annual budget for the assisted living/nursing home we’ve covered a lot of medical expenses already. Simply make sure you don’t completely run out of money if you live to age 98+ and leave a large inheritance if you die earlier! We can always look at what’s the historical distribution of the final value and check what are the probabilities of a final value >$1m!

How do we implement the supplemental cash flows from Social Security etc. in the spreadsheet? Let’s take a look at the tab “Cash Flow Assist” (ignore the part about the CD ladder, we’ll deal with that later!)

- Social Security

- Becky’s own benefits in month 35: +$990

- Becky’s own+spousal and Stephen’s benefits in month 68: +$1,330 and +$3,500, respectively.

- 17 years into retirement (month 1+17*12=month 205), when Becky and Stephen are in their mid-80s, they will scale back their expenses by $10,000 per year. This will show up as a positive cash flow of $833/month

- 21 years into retirement (month 1+21*12=month 253), one spouse passes away. Becky’s SS benefits go away.

- 25 years into retirement, sell the house. Let’s assume that the $450k house maintains its value in real terms, i.e., appreciates in line with CPI. But also assume broker and other transaction costs of 8%=$36k. Net proceeds=$414k. The surviving spouse moves into an assisted living facility. This will raise the annual budget from $70k to $150k, so we enter a negative monthly cash flow of $6,667 starting in month 302.

- Taxes: See this post on how Social Security is taxed on the federal return.

- Until Stephen claims his Social Security: Assume $8,000 p.a. So, I enter -8,000/12=-666.67 in the first 67 months.

- For the next five years, let’s assume taxes are a bit lower because we’re done with the aggressive Roth conversions. $5,000 p.a. (very conservative, likely lower in real-life), so I enter -$416.67 in months 68 to 127

- After that, your tax liability drops to $3,000 p.a. That is again quite conservative because it’s likely that you will have depleted your taxable savings and rely on Roth contributions plus Social Security (plus a few T-IRA distributions). $3,000 tax liability, again quite conservative, so I enter -$250 in months 128 to the end. Colorado does tax your income with a flat tax of 4.63% income but it has some generous exemptions ($24k per year for 65 years and older). Note: I’m not a tax expert. I’m not a Colorado resident either, so I have to rely on data I found online. I normally use the Kiplinger State-by-State Guide to Taxes on Retirees.

Wow! That’s a mouthful! Let’s summarize the cash flows over time:. The Google Sheet searches for the initial safe consumption amount x (set to $80k in this example). Note that I didn’t display the large cash flow from the home sale which would show up as a “negative withdrawal” but it would blow up the scale! 🙂

A quick technical note: The way I set up this case study is to do the Safe Consumption part for the first 25 years only, so playing around with the initial withdrawal amount x has no impact on the flows after month 301 when the cash flows are predetermined at +3,500 Social Security, $-12,500 for the nursing home and $-417 for taxes. To implement this in the Google Sheet I set the “scaling of withdrawals” to 1 for the first 25 years (months 1 through 300) and to 0 starting in month 301.

And another side note: a common question I get is how I deal with inflation in my calculations. All of the cash flows I’ve mentioned are in 2019 dollars, so in the calculations, I assume that they will go up with inflation. Thus, they are entered in the section labeled “Cash flows that will be adjusted by Inflation (e.g. Social Security, public Pension, etc.): Enter in today’s $”

Detailed results

First of all, forget about the 4% Rule. The initial consumption rate is much higher, closer to 7% and you can afford this in light of the substantial Social Security benefits just around the corner. Here’s the table with the safe withdrawal rates in the main tab of the sheet. It turns out that the overall worst failsafe was 6.60% (though that would have been pre-1920). After 1926, 6.73% would have been OK, which translates into more than $90k!

I also display the safe rates by market event and by decade (1920s and forward) below:

If you prefer to see these numbers in dollar amounts you can also see the same tables as dollar figures in the tab “Cash Flow Assist,” see the table below:

So, it looks like $80,000 annual consumption (plus the provisions for taxes!) is ironclad and super-safe. And again, this $80k budget is for the first 17 years, scaled down to 70k until year 25 and then $150k for the remainder. But that doesn’t mean it was a smooth ride! Let’s take a look at three prominent bear market scenarios:

- (1/1916: let’s ignore the pre-1929 experience for now. This was the worst experience in a previous version of the case study)

- September 1929 is the market peak right before the Great Depression!

- December 1968 is the cohort worst hit by the tumultuous 1970s and early 80s! If you remember last week’s post, this is one of the worst bear markets in history when measured by how long it took to recover!

The chart below plots the value of the portfolio (adjusted for inflation) of the three disaster cohorts over their 35 years of retirement. Notice how they all survive the 35 years and have about $800 (1916) and all the way up to the desired $1m+ (1929, 1968) as the final value. But it was a rough ride! All three cohorts drop below the $600k mark, two of them even below $500k only to recover again to the seven-figures club, especially after the massive cash inflow in month 300 due to the home sale.

How likely is it that you still have a $1m cash cushion at age 98? In the Google Sheet, I created a tab “Distribution of Final Value” to study the distribution of the final values for the historical cohorts. I sorted the final asset value (expressed as multiples of the initial value) from lowest to highest (though in the chart I go only up to the median = 50th percentile) and plot it in the chart below. So, I can read off, what’s the probability of falling below a certain final value, especially in the left tail of the distribution!

For the math/stats geeks, this chart is essentially the historical “cumulative distribution function (CDF)” but with the axes flipped! 🙂 In any case, historically you would have had a roughly 5% chance of ending up with less than $1m and a 14% chance of ending up with less than the initial portfolio value. It seems like $80k is a pretty solid withdrawal strategy that a) never would have run out of money in past cohorts and b) had a reasonable probability of maintaining the portfolio over time. Though, again, I like to stress that a lot of historical cohorts had massive drawdowns along the way, especially if the market was weak during the first six years!

Recommended withdrawal sequence

The SWR Google Sheet just considers all the different accounts as one single big portfolio. In practice, however, we still have to determine what accounts we like to tap in what order. My recommendation:

- Withdraw the taxable bonds, cash/money market first. This should suffice for about 3 years worth of expenses and taxes. Then liquidate taxable stocks.

- Because you’re withdrawing the taxable assets with a very high tax basis first, you should realize only very minimal taxable income. Use the “space” in the standard deduction plus the 10% federal tax brackets and even a bit of the 12% bracket to do Roth conversions. You should be able to do around $50k every year until Social Security starts. The idea here is that you want to make a meaningful dent in your Traditional IRA. But don’t go completely bonkers with the Roth conversions because we can still withdraw a small amount of the T-IRA tax-free even when Social Security kicks in. Being too aggressive with the conversions would mean that we leave those tax-free IRA withdrawals on the table!

- Also, notice that your annual standard deduction is raised by $1,300 per person above the age of 65! Use that to max out your Roth Conversions!

- Once Social Security kicks in, we have to go through a pretty arcane calculation to figure out how much of those benefits are taxable on your federal return. Initially, I worked under the assumption that it’s 85%. But the calculation is more complicated. It turns out that even with $58k in annual Social Security benefits, the fraction taxed on your federal return is a lot less than the 85% I assumed. We can even hack this so that your T-IRA withdrawals still fall into the standard deduction. See the post on 11/20/2019 about the recommended Roth Conversion strategy.

- Required Minimum Distributions after age 70.5 (the age could potentially be lifted from 70.5 to 72 if the Secure Act passes, see Forbes article here!) shouldn’t be an issue. The RMDs will likely be lower than what you withdraw to fill up your Standard Deduction.

The calculations for how fast or slowly you should convert are a bit too involved to add here to this already very long post. (and by the way, I’m the Safe Withdrawal Rate dude, not a tax expert!!!) I will write a new post on this Roth conversion conundrum, probably by next week to update everyone!

Also, notice that one of the common challenges of the extremely early retirees doesn’t apply here! Becky and Stephen are past age 59.5 and can tap all of their retirement savings penalty-free (though not tax-free). So, there are none of the cash flow hassles we normally face where you have to make sure you have enough taxable accounts and/or Roth ladders with the 5-year lag between conversion and withdrawals!

By how much can they increase their budget?

After I finished the study and told Becky that it looks like their $80k a year budget is a “go” she asked me if they can up their budget to $90k. Well, we know from the tables above that the failsafe consumption amount was just under $90k. What cohort would have run out of money consuming $90k? You guessed it: 1968. In the chart below I plot the time series for that cohort under an 80k, 85k and 90k annual consumption budget, respectively. It turns out, the 1968 cohort was the one that will not digest the cash flow pattern that Becky and her husband plan very well. You’d have almost run out of money toward the end. More worrisome than that, though is fact that the 1968 cohort would have depleted their portfolio to all the way down about $400k after 25 years. Adding the home sale would have brought you up to a bit over $800k in month 300. It’s only because of the start of a major bull market of the 1990s that you even made it that long with $150k of nursing home expenses per year! So, for me personally, moving into a nursing home with such a small nest egg would not make me very confident and comfortable. Maybe start with $85k and see how that goes for the first few years!

Use a glidepath?

As I pointed out in Part 19 and Part 20 of the SWR Series, one way to alleviate the impact of Sequence Risk is to use a “glidepath,” i.e., start with a lower than long-term sustainable equity weight but then shift back into equities over time. One way to implement this is to shift, say, $300k into a CD ladder. Let’s assume you get around 2.25% nominal interest. Over a 72-month period before Social Security kicks in that would get you about $4,450 per month. So, we reduce the portfolio by $300k to $1,055,000 but we compensate for it by adding the positive nominal cash flow in the Google Sheet, see below.

You now have an initial allocation of 47/27/26 Stocks/Bonds/Cash, only to shift back into the long-term target allocation of 60/35/5 over time once you reach Social Security. Would that have saved the 1968 cohort? You bet! But again, you would have moved into the nursing home in year 26 with an extremely depleted portfolio. Still not a very comforting scenario. But it’s good to see that the glidepath at least alleviates some of the Sequence Risk during the first six years!

Other thoughts

There will be a large cash infusion when you sell the house. I assume it’s $414k in today’s dollars (after 8% transaction costs). What do you do with this large cash infusion? Currently, I assume it goes back into the nest egg (taxable account) at the prevailing 60/35/5 allocation. Sometimes people are too afraid to invest such a large lump-sum, see the discussion on lump-sum investing vs. Dollar-Cost-Averaging (both here on the ERN blog and in my initial ChooseFI appearance, Episode 35). One alternative would have been to build a bond or CD-ladder (see my CD ladder toolkit!) to take the home sale proceeds and fund the first several years of the nursing home with that. That’s certainly feasible and also desirable (it lowers Sequence Risk) but it’s also impossible to forecast the interest rate landscape that far into the future. It’s a battle that’s best fought at that time.

And again, in case I haven’t stressed this enough, be prepared to draw down the portfolio, at least initially. If the market is weak over the first six years and you withdraw 6+% p.a., then you will very likely draw down the portfolio. If the market is really bad you might draw down all the way to $500k!!! But don’t despair! Because your withdrawals will be so low once SS kicks in, you’ll have plenty of time to recover!

Conclusions

As I said on the podcast already, it looks like Becky and Stephen should have a safe and comfortable retirement. They can even raise their budget a little bit. Though, I’d be cautious about going all the way to $90k per year. Maybe start with $85k for a few years and see how things work out.

In any case, I learned a lot from doing this exercise. First, you’re never too old to get your financial act together. All of the principles of FIRE apply here, too. Even at 50 years old you can still shoot for a comfortable retirement in your early 60s, way earlier than most other Americans. I’m so grateful to Jonathan and Brad for bringing Becky on their show because we all benefit from having a more diverse FIRE community. FIRE in general and ChooseFI, in particular, are all great sources of inspiration and information for all age groups!

Second, “older early retirees” (if there’s such a term) have a number of advantages: higher Social Security benefits due to more years paying into the system, less time until benefits start and also less political uncertainty about the size of your benefits. The shorter life expectancy, while obviously nothing to cheer about, is also at least a mathematical advantage over the extremely early retirees. So, the initial consumption rate is much closer to 7% here in this case study! Another example where the Trinity Study and the plain old 4% Rule is of no help. You have to get your hands dirty and make this a customized and personalized safe withdrawal analysis!

I am also encouraged that the prospect of some large future assisted living and nursing home care expenses does not sabotage their comfortable early retirement. Take that, Suze Orman!

Best of luck to Becky and Stephen!

Absolutely brilliant. As insightful as ever ERN!

Thanks for sharing the methodology in so much depth, SO helpful!

As you said, once you’ve won the FI game, why would you keep gambling?

Thanks J! 🙂

wow – this is great stuff. Thank you for taking the time to review and share this information. We are in our 40s with a nice nest egg already plus 2 pensions in our future so I am thinking we may have achieved FI if we could figure out all the scenarios.

Thanks!

With pensions and SS, you’ll be surprised how much less you need than 25x now.

Just plug in your numbers in the Google Sheet and see where you are now! 🙂

Couple comments: I’m not sure I would assume their social security will be 85% taxed. They need to calculate their combined income for social security purposes (1/2 of SS, plus AGI, Plus muni bond interest) and see if that get’s them above the 44k mark for 85% taxation.

In addition, it is not wise to fully convert your pre-tax accounts. If you do that, you will not have enough ordinary income to utilize your standard deduction in retirement. What that means is you are giving up getting pre-tax money at 0% taxation (the holy grail!) in order to do Roth conversions at 12% taxation now!

Likely they will want to do some partial Roth conversions and some cap gain harvesting. Luckily, the TCJA expires after 2025 right about when they have to concern themselves with SS taxation, so they have a great Tax Planning Window to get some partial Roth conversions done!

Yeah, you’re right, they might back off from their Roth conversions. SS is only factored in as 1/2*SS in the IRS forumla. So future income past age 70 will not be taxed as heavily on the Federal return. There may not be a great need to be so aggressive with the Roth conversions!

Good stuff , this mirrors our situation pretty closely in 5-6 years. I do think you spousal SS number is a bit high. Remember the Spousal benefit is up to 50% of the higher earners FRA amount (PIA), which appears to be closer to $1,500/mo

If Stephen is 64 in 2019, he was born in 1955. People born in 1955 have a FRA of 66y+2m. If his SS benefit @70 is $3500, his PIA would be about $2690. Half of his PIA ($1345) is the max spousal benefit when Becky reaches her FRA at 66y+4m (born in 1956).

Gotcha. I will write a corrected version with the right SS numbers! Thanks!

Very good point! When you take spousal benefits before your full retirement age you are penalized for that. But it appears that if you wait until after your full age you don’t get the boost in the benefits you’d get when delaying your own benefits.

I updated the numbers. But since Becky can also claim her own benefits before that, the impact on the SWR was about a wash.

As always, great post ERN! Two comments: (1) not sure you implied this or not, but the 50% spousal SSA benefits stops increasing once the FRA of the higher earner is reached. There have been recent changes related to spouses “filing and forgetting” technique based on age as well (Becky & Stephen might qualify but I am no tax expert either); (2) Maybe some mental gymnastics on my part but as I begin doing Roth conversions for the next few years I will consider any market downturn to allow me to move more shares from pre-tax to post-tax in any given year effectively allowing me to move more $ per year – money is really fungible if you think in terms of shares of a given fund/stock.

Both really great points. I changed the spousal benefits calculations in the post to reflect that.

Second: You definitely “benefit” from a market downturn when you do Roth conversions exactly in the way you describe. So, as bad as a bear market may be, there is a small tax benefit. Excellent point!

Becky will get half of his PIA, what he would receive at his full retirement age, not half of what he is drawing at 69.

Gotcha. I will write a corrected version with the right SS numbers! Thanks!

when did the RMD age change?

https://www.forbes.com/sites/forbesfinancecouncil/2019/08/15/the-secure-act-three-takeaways-for-ira-owners/#2c35fb0f265a

“Currently, retirement savers who use traditional IRAs are required to start taking required minimum distributions (RMDs) from their retirement account at 70½. (RMD rules do not apply to Roth IRAs while the owner is alive.) The SECURE Act would push back the age at which RMDs must begin to 72. Raising the RMD age would give investors another year and a half to enjoy tax-deferred growth of their IRA investments.”

This Act has bipartisan support in the House, but it’s stalled in the Senate. It might very well pass before B&S get to age 72.

This was terrific especially because it almost exactly matches my age / retirement horizon / budget needs. Early 60s, 35-year retirement / $90k expenses. I know your blog is mostly oriented toward younger FIREs, but thanks ERN for this case study. I believe you have a substantial audience of those in my category. And your younger FIREs will eventually be joining us. 🙂

Thanks!

Yes, as I said, let’s not exclude anyone here. FIRE at any age is a great accomplishment and there are fascinating math problems involved! 🙂

Like Becky and Stephen – I’m in the same situation – I also have taxable bond funds in my taxable account to produce available monthly income without touching my Roth, Trad IRA, and 401K accounts, since I wanted to withdraw from those last in order to take advantage of the long-term compounding return effect on the stock funds in those accounts. So I have some stock funds in those tax-deferred / tax-free accounts. But now as you say, since money is fungible, I’m thinking of following your advice above and moving all the taxable bond funds into the Roth, Trad IRA, and 401K accounts and having all the stock funds in my taxable account. Although I will pay some capital gains taxes on the stock funds in my taxable account if they have gone up, but still ahead on the gain. The bond funds in my Roth, Trad IRA, and 401K won’t compound as much, but I’ll get the same compounding effect in my taxable account.

Is my understanding of your advice correct?

Yes, that’s what I envisioned.

Before you do anything rash, make sure you don’t realize any large gains in that initial

transaction.

Becky and Stephen have some bond funds in a taxable account with minimal capital gains. It’s OK to liquidate them and do the switch.

Also notice that your newly acquired stock funds in the taxable account will now have a very high basis. If the market goes down you can use tax loss harvesting. If the market goes up you owe only minimal taxes on capital gains (but make sure they are long-term!!!).

Thanks. I did the switch. No capital gains on the sold bond funds from my taxable account. In fact a small loss to harvest. 🙂

Now here’s an interesting question: there is an iShares short-term treasury bond ETF SHV in my taxable account. I know that treasury bond interest should be tax-exempt from New York State’s 6.7% hefty income tax (yikes!). However I can’t get a clear answer from either Fidelity broker or iShares customer service as to whether they are able to report on my end-of-year 1099 that the interest from SHV should be exempt from NYS tax. If they can’t then I should switch it to tax-advantaged accounts. Have you or any blog followers had any experience with holding treasury bond ETFs in taxable accounts and being able to take advantage of the state tax exemption on the interest? Thanks!!

For that you’d have to ask your tax experts! 🙂

Wow What an awesome detailed analysis! The one thing im confused with for myself is how the spousal benefits work. Ive read up on the subject and am still confused hoping you can clarify.

Im 49 and my wife is 50. We were planning to take soc sec with me at 70y/o ($30k). My wife at 62 ($10k) If my fra number is approx $24k at 67. How do we go about filing this to maximize the spousal benefit rule?

Thanks

I messed up the spousal benefit calculation.

The best calculator I’ve seen is the one I noted above in the updated post:

https://opensocialsecurity.com/

Well, I learned something new from the comments today.

Carry above wrote: “Becky will get half of his PIA, what he would receive at his full retirement age, not half of what he is drawing at 69.” Not sure if she meant him drawing at 69 or 70.

So my question is whether it’s really worth it for the higher earner to wait until 70 to file for the SS benefits if his/her younger spouse with smaller life-time earnings will not maximize SS earnings beyond the FRA of the higher-earning spouse.

Would anyone have any opinion about this? I don’t know how much exactly SS benefit increases per year by waiting, but it increases less than 8% I think. Of course, it depends on the personal circumstances like health, life expectancy, wanting or not do deplete more of the pre-tax retirement savings before RMD’s start, etc.

TY

Thanks!

https://opensocialsecurity.com/ has the answers to the spousal benefit timing issue! 🙂

Excellent analysis, but I think I may have misunderstood the glidepath and asset allocation part. I thought shifting to higher equities was the ideal path, yet here you suggest maintaining 40% of the portfolio in cash or bonds. Isn’t this the exact proposal you flagged as being maximal risk in the SWR series? How can shifting to higher equities here (80%+) increase their risk of running out of money when it’s exactly what saved the worst cohorts in earlier SWR simulations?

I’m obviously missing something…

Good point.

This particular case is not the perfect example for the style of GP as I described in Parts 19/20.

I played around with a changing final asset allocation with stock shares >60% (post glidepath) and they didn’t really improve the fail-safe. So, I left it at 60% stocks.

That’s because there would be two Sequence Risk events: 1) the initial withdrawal phase and 2) the large boost in withdrawals in year 25. So, ideally you’d do a GP early on and then a “bond tent” around year 25.

ERN,

I’m struggling to figure out how to model my situation in the spreadsheet. I’ll retire and she’ll keep working for a few years. Let say she earns $70k income but our expenses total $100k. I plan to pull the $30 from my IRA (I will be 60 y/o). Would I enter -30000/12 as negative cash flow during these months?

Thanks!

I’d do it the other way around: Target $100,000 per year in consumption (potentially gross-up to account for taxes), but include the wife’s income as a positive supplemental cash flow. And do so for as long as she still wants to work. So, enter 70000/12 per month! 🙂

Is $150K the average annual expense for a nursing home scenario. SInce the house is already sold and the survivor has no assets would Medicare not kick in it the $150K gets exhausted?

I found $150k really high. This budget will get you a really posh facility.

If your money runs out and you go to government-run facility it’s probably a less dignified experience and apparently they want to avoid that.

ERN – I really like your analysis and how you presented it in the post.

I can provide a current reference point for actual nursing home costs. Both of my Parents are being cared for in a skilled nursing facility. It is considered to be high quality, and is part of a nonprofit Continuing Care Community located in Pennsylvania. The annual fees for the skilled nursing are currently $156K each. My Parents did not pay an entry fee, and so are paying the “full rack rate”. The cost for assisted living for one person at the same community is $139K (again the full rate – no entry fee). When we were researching assisted living/skilled nursing facilities, we did visit two that had primarily Medicaid funding, and found that they were less than ideal. This experience has reinforced to my wife and I that we should continue to include a budget in our financial plan, for long term care (to cover assisted living and skilled nursing), with an assumption that both of us could require such care for five years in a high quality community. We may get lucky, and not require this level of care. However, with advances in medicine, medical technology, and healthier lifestyles, many people will live longer, and may require higher levels of care at the end of their lives. My Parent’s other required expenses are less than $750.00 per month combined.

Wow, thanks for prividing those numbers! That’s shockingly high! One of the reasons why I budget conservatively with our numbers.

But $150k+ would almost entice me to move to another country, e.g., Philippines. Even some European countries will be cheaper than that!

Hi Big ERN. Excellent article. I really like that it doesn’t “smooth out” the whole retirement window as one, but instead looks at it as separate windows due to financial events, e.g. SS kicking in, selling the house, etc.

A question for you though, since it is best to keep taxable bonds in a tax favorable account (IRA, etc), doesn’t the same logic apply to the CD ladder? I.e. The CD ladder should be in a tax favorable account, and use the fungibility of money to sell stocks from the taxable account and convert some of the CDs (upon maturity) into the same stocks that were just sold? In other words, try to keep all income producing products in a tax favorable account.

Thanks

Slight clarification above: I assumed, but didn’t state, that the CD ladder has maturity dates in it that coincide with when the stocks need to be sold in the taxable account, therefore a CD has been converted to cash just as stocks need to be sold in the taxable account to provide living expenses. Then, the sell in the taxable account and the purchase in the tax favorable account are wash sells.

Yup, correct! No need for clarifying, that seemed obvious to me! 🙂

Yes, absolutely, the same logic applies here too. For tax-efficiency, keep the CDs in the IRA and then do the switcharoo as you described! 🙂

Great post. Do you account for the ROTH conversions in the spreadsheet anywhere? My own case study is very similar, but plan on working first 10 years part time, so it makes the ROTH conversions a bit more detailed.

I haven’t done a detailed analysis of the Roth conversions. And since there is this issue and my confusion with how much of SS benefits are taxed later in retirement, I’m glad I didn’t go into too much detail.

I’ll write another update in the next 1-2 weeks on my ideas for this issue.

But it will involve still the same 2 ingredients: Aggressive Roth conversions for the first 6 years, but keep a small amount in the 401k/T-IRA for later because it turns out that not all of the Standard Deduction will be exhausted by the SS benefits later in retirement. 🙂

Another gem in the SWR series. These posts have been so incredibly interesting, insightful and helpful. Thank you!

Quick question about the spreadsheet used for this case study. I found it interesting that the target SWR for the 0.00% failure rate scenario shows 6.77% (CAPE > 30), which happens to be higher as compared to the 6.65% showing for CAPE > 20 (I am looking at the “Parameters & Main Results” tab). I would have expected the SWR to be lower when the CAPE is higher. Thoughts on why this is happening?

Again, thank you for publishing the SWR series!

Yeah, that’s because some of the lowest withdrawal cohorts occurred when the CAPE wasn’t even that high (pre-1920s).

But it’s still true that some of the still-really-bad cohorts post 1920 were the ones retiring when the CAPE is high (>20)!

Great point! You got good eyes! 🙂

Another great post Big ERN! I’m wondering if you’ve ever used a high fidelity retirement calculator such as PRC Gold (https://pralanaretirementcalculator.com/html/pralana_gold.html) to do one of your SWR studies? I was introduced to the product in a post by Darrow Kirkpatrick of Can I Retire Yet. I have absolutely no financial interest in the company. It appears to do everything your Google Docs spreadsheet does and much, much more. I love the detailed federal and state tax calculations which takes much of the guesswork out of Roth Conversion questions. The calculator is not free but I have found it to be very useful in my planning. Just curious if you’ve looked at this or similar products and what you think.

I checked it outt, but only the Bronze (free) version.

Strange that you can run Monte Carlo sims where you assign the expected return, but no Variance-Covarnace matrix. Doesn’t feel right.

I also don’t like the annual frequency because you miss the 1929 mid-year peak if you do the historical analysis.

Also cautious: I doubt that this tool goes through the whole detailed analysis of Roth conversions, as you open a whole can of worms with the tax torpedo issue, see this week’s post!

But overall it looks like a nice tool. I wouldn’t pick it as my ONLY tool. I still prefer my own methodology.

Hi Karsten,

What a fantastic post! I think this particular case study has so much useful information for us “older” early retirees. I especially enjoyed listening to the podcast. You are able to explain things clearly and simply, but you never dumb it down. I hope you do more podcasts in the future.

Thanks! Glad you enjoyed the post/podcast!

Yeah, all the same principles apply to 28-yo early retirees and 62-yo retirees. Some of the math even gets easier! 🙂

If one were to have bonds in tax deferred accounts, how do you access it if the first few years the market dips? Especially for early retirees when you spend the money in taxable first.

Hi Kevin.

If you look back at my comment above, and Big ERN’s article in regard to fungibility of money, I think that would help. Basically, you do a “swap”. As an example, say you have $100k in bonds in a tax deferred account, and $100k in an index fund in a taxable account. Now you need $10k. You sell $10k of the index fund in your taxable account (paying cap gains taxes). In your tax deferred account, you sell $10k of Bonds and buy $10k of the index fund you just sold from your taxable account. Your end stated is $90k bonds, and $100k index fund, which is what you wanted. The nuance is that the index fund is now $90k in your taxable account and $10k in your tax deferred account.

I hope that helps

Hi Billy,

Thank you for replying. I think I get it now. For example, if during my first year of retirement, the market goes down 20%. I need 40k of withdrawal from my taxable account to cover the year of expenses. So I sell shares to cover the $40k, but then I immediately sell some bonds in my tax deferred to buy back whatever I sold in my taxable in my tax deferred account.

This makes sense and the numbers add up.

However, my follow up question is, wouldn’t the money in my taxable be depleted much faster (vs holding bonds in taxable, eg bond tent) and therefore the definition of SORR?

Thank you.

Hi Kevin,

The reason for keeping the bonds/CDs in a tax advantaged account is that they produce taxable income, versus dividends/capital gains which are taxed at a lower rate. You want to defer paying income tax as long as possible, so the higher taxed assets are held in the tax advantaged account.

You may or may not deplete the taxable account faster. It depends on the market. If the market is down early (SRR), then yes, it would deplete faster. However, your goal isn’t to protect the taxable account, but to protect all of your assets while minimizing taxes. The strategy above has you at the same end state just split across taxable and tax-advantaged accounts, while delaying taxes as long as possible.

Thank you Billy!

I guess it’s not so much of a SORR problem, but cash flow problem if you deplete taxable too quickly.

Food for thought, if say you deplete the taxable quickly due to market downturn, and have to eat into your Roth, isn’t this bad? since Roth is the last account you want to withdrawal from deally.

Again, money is fungible. In exchange your Roth IRA grows tax-free for future tax-free withdrawals.

Nice explanation! Thanks! I should hire you as my moderator! 🙂

BIG ERN:

Another absolutely amazing case study. Just fantastic work. I really found this case study relevant given the various stages of their retirement. Thank you!

In all honesty, I have to read and re-read your work because it is so detailed. I am still not completely sure that I understand how you have accounted for inflation. 🙂

Thanks!

All my studies ALWAYS account for inflation. It’s more elegant to keep expenses constant in real terms but then use real, inflation-adjusted returns. It’s equivalent to using the more cumbersome method where you have to CPI-adjust everything. See my post here for an explanation of the equivalency of the two methods:

https://earlyretirementnow.com/2018/02/28/inflation-risk-for-early-retirees-part-2/ (section “How I account for inflation in my Safe Withdrawal Rate Series”)

Thank you BIG ERN! I realize my question was pretty basic but I wanted to make sure that I understood how inflation was addressed in your work.

The thoroughness and detail of your work is remarkable. I know I have posted this before but I believe you have found your next side hustle. Set up shop preparing customized SWR reviews and plans of action like these for readers. You would make a killing!

Haha, I thought about that. It’s a lot of work. But I might get a hang of it and offer it at some point! 🙂

Do please consider it.

Could lessen the work by building a template for clients to standardize their inputs.

And I’d guess even a cursory review (20% effort) would give clients 80% value? You could then direct them to an endorsed specialist for additional work.

Thanks in advance.

You could crowd source advice for situation on the forum on here or one of the many popular early retirement forums.

Interesting idea. The more “serious” route would be for people to work one-on-one, though. Not sure everyone would be willing to open their “books” to a bunch of “strangers”

Sure, could provide blog content as well as income.

Maybe model the service something like Rick Ferri’s Portfolio 2nd Opinion, but with an emphasis on withdrawal and Roth conversion strategies.

https://rickferri.com/investors/

https://jonluskin.com/portfolio-2nd-opinion/

Take my money.

Yes, thanks! This would be the kind of service I’d like to offer IF I ever go this route. None of the traditional AUM-based asset management you’d normally see in the RIA community.

Very nice work.

Was especially happy to learn about the possibility to deal with the predetermined future cash flow by setting the scaling to 0 at that point.

Though not particularly important, the cohort that caused the 90k consumption to fail was not the 12/1968 one, but the 07/1911 one.

OK, got it. Not that it matters, but you’re right: Now 1911 has the lowest SWR. But post-1920s it’s still 1968 with the worst performance.

Your comments regarding keeping taxable bonds in a tax deferred account are interesting. Wouldn’t you need to be wary of triggering a wash sale? I was just reading up on that and ran across this: “If you sell shares in your taxable account and buy substantially identical shares in your IRA within 30 days, the wash sale rule applies. It also applies if you sell shares in your taxable account and buy within 30 days financial instruments that can convert into the sold shares”

Very true. After you harvested a loss you can only invest in sufficiently different funds in ALL ACCOUNTS, i.e., including retirement accounts. That also refers to dividend reinvestments!