November 16, 2021 – My Safe Withdrawal Series has grown to almost 50 parts. After nearly 5 years of researching this topic and writing and speaking about it, a comprehensive solution to Sequence Risk is still elusive. So today I like to write about another potential “fix” of Sequence Risk headache: Instead of selling assets in retirement, why not simply borrow against your portfolio? And pay back the loan when the market eventually recovers, 30 years down the road! You see, if Sequence Risk is the result of selling assets at depressed values during an extended bear market, then leverage could be the potential solution because you delay the liquidation of assets until you find a more opportune time. And since the market has always gone up over a long enough investing window (e.g., 30+ years), you might be able to avoid running out of money. Sweet!

Using margin loans to fund your cash flow needs certainly sounds scary, but it’s quite common among high-net-worth households. In July, the Wall Street Journal featured this widely-cited article: Buy, Borrow, Die: How Rich Americans Live Off Their Paper Wealth. It details how high-net-worth folks borrow against their highly appreciated assets. This approach has tax and estate-planning benefits; you defer capital gains taxes and potentially even eliminate them altogether by either deferring the tax event indefinitely or by using the step-up basis when your heirs inherit the assets. Sweet!

So, is leverage a panacea then? Using leverage cautiously and sparingly, you may indeed hedge a portion of your Sequence Risk and thus increase your safe withdrawal rate. But too much leverage might backfire and will even exacerbate Sequence Risk. Let’s take a look at the details…

Some preliminary calculations

Let me first demonstrate how attractive the leverage strategy looks on paper, especially when focusing on the final portfolio value only. In the chart below, I plot the final value of both a 75%/25% and 100%/0% stock/bond portfolio after 30 years in the absence of withdrawals (i.e., buy and hold). This is for cohorts retiring between 1925 and 1990. I adjust the portfolio value for inflation using the CPI index, as usual. Quite an impressive performance. For the 75/25 portfolio, the final value ranged from $2.63 to $13.25 per dollar of initial capital. That’s a geometric average return of between 3.27% and 8.99%. For the 100% equity portfolio, the worst-case outcome was a 3.23x multiple and in the best-case scenario, the portfolio grew more than 26.4x. So, even in the worst-case scenario you still had a 3.99% real return in your equity portfolio.

If we want to model the safe spending amount when using a margin loan to fund our retirement expenses, we’d have to make assumptions about two major parameters:

What’s the interest rate for that loan? Let’s assume that over a 30-year retirement horizon, we have access to a line of credit and/or a portfolio margin loan at a (fixed) real rate. Just as a reference, Interactive Brokers which offers the most competitive margin rates (to my knowledge, at least), currently offers margin rates on a tiered system between 0.3% and 1.5% above the effective Federal Funds Rate, with the lowest interest tier starting at balances above $3m. This is for their “IBKR Pro” account.

For very large loan sizes ($4m+) you can indeed push that weighted spread to around 0.5%, but between $1m and $2m we’re looking at closer to 0.75 to 1.00%. Let’s work with a round number, 1%! If we assume that the long-term forecast for the Fed Funds Rate is 2.5%, the long-term CPI inflation forecast is 2%, and the IB spread is 1%, then we should be able to borrow at about 1.5% above inflation from our brokerage account. But I want to keep an open mind about how high or low that interest rate would be, so I will use three alternative real rates: 0%, 1.5%, and 3% just to see how sensitive the results are.

Side note: I can already hear the complaints: The most recent CPI headline inflation number was 6.2% year-over-year and I can borrow at IB for 1%. Shouldn’t I use a -5% real interest rate then? Well, you could but don’t assume that these attractive terms will last. The FOMC will likely bring interest rates back to 2.5% or above by 2024 and inflation should stabilize at around 2% before too long. Don’t extrapolate the ultra-low interest rates much beyond the next few years.

What’s the maximum size of the loan at the end of the 30-year horizon? No bank would give us a loan worth the entire 3x initial capital. Interactive Brokers, for example, mandates a minimum 25% margin requirement for stocks and mutual funds. In other words, if we start with a $1m portfolio that grows to $3m after 30 years, we’d need at least $750k net equity in the account at T=30, limiting the loan to “only” $2.25m in the final year. But even that is pushing it. Prudent investors would likely target a much lower leverage ratio for several reasons:

- There is no guarantee that brokerages and regulators will keep a promise of letting you borrow an additional $2.25m for the $750k net worth in your account. What’s worse, the greatest risk of regulators and brokerages cracking down on margin constraints always seems to come up during the worst market drawdowns. When it rains it pours!

- Most retirees will not hold their entire net worth in a taxable account at Interactive Brokers. More likely, you will hold a whole range of accounts: taxable, 401(k), IRAs, Roth IRAs, HSA, etc. But only the taxable accounts are marginable. To the best of my knowledge, you cannot borrow against your retirement account, at least not directly from your broker. Maybe a bank will give you a loan, but probably not at terms and rates comparable to the IB margin loan.

So, if you start with a $1m portfolio and figure it will grow to at least $3m after 30 years, let’s see how much of a “safe withdrawal rate” we can generate through a loan. I calculate that for different loan targets and real interest rates in the table below.

So, to summarize the calculations so far, if you start with a $1m portfolio and budget for a $3m worst-case scenario final portfolio value after 30 years, you could pull off a “safe withdrawal rate” of somewhere between 3.96% and 5.28% when facing a 1.5% real margin rate and you target a final loan size between $1.5m-$2.0m. That’s pretty amazing because this would imply a 5.28% safe withdrawal rate with capital preservation! In contrast, you’d normally just scrape by with a 4% Rule and a zero final portfolio target. What’s not to like about this approach then?

Well, the problem with the margin requirement is that it has to be satisfied not just after 30 years, but at all times along the entire retirement horizon. Let’s see how that would have worked out in some of the Sequence Risk worst-case scenarios.

A 1965 Case Study

The mid-to-late 1960s were a true nightmare from a Sequence Risk perspective. That’s because both stocks and bonds had underwhelming returns in the late 60s and early 70s, followed by three bad recessions in 1973-1975, 1980, and 1981-1982. Because of both the length of the low return phase and the depth of the mid-70s and early-80s recessions and bear markets, the 1965 retirement cohort is often considered the worst-case scenario, often worse than even the Great Depression!

So, let’s look at the November 1965 cohort and assume that this cohort had started with a $1m portfolio. In the chart below, I plot the buy-and-hold portfolio values for both a 75/25 and a 100/0 asset allocation. I also plot the size of the loan, both for a 1.5% and a 3.0% real loan interest rate. The reason I also plot the 3.0% interest rate line is that during the 1965-1995 time span, the real, CPI-adjusted Federal Funds Rate was about 2.1%, so if we add a 1% loan spread, we’ll indeed arrive at a 3% real margin loan for that 1965 cohort. Of course, there is no way of telling what margin rate anyone could have gotten around that time. I suspect that the conditions would have been less attractive than today. That’s the main reason I ignore the 0% real borrowing rate for now! A rate that low would have been difficult to get during that time!

After 360 months, the leverage strategy would have indeed worked out splendidly. The loan of $1.5m and $1.9m for the 1.5% and 3.0% margin interest loans, respectively, could have easily been paid off by the final portfolio of close to $4m. But do you notice a problem with this calculation? Somewhere around 180-200 months into retirement, during the 1982 recession and bear market, your portfolio value dropped below the loan balance. Not just for the 3.0% real rate but even for the 1.5% real rate loan assumption. Well, that’s a problem. You would have wiped out your portfolio and actually run out of money after only about 15 years. And by the way, the subsequent recovery of the portfolio during the 1980s stock market rally is irrelevant. You would have gotten a margin call from your brokerage, forcing you to liquidate your assets. And you would have gotten a bill for any potential shortfall!

That’s bad news! Most of the failures of the 4% Rule in unleveraged portfolios and over a 30-year horizon would have occurred much farther into retirement, usually past the 26-year mark. Using leverage to hedge against Sequence Risk actually made everything worse. You never liquidated a single dollar from the portfolio for over 15 years, but then you were force-liquidated exactly at the bottom of the 1982 recession.

Leverage exacerbated Sequence Risk in this case!

A 1929 Case Study

We can plot the same thing for the September 1929 cohort that retired right before the stock market blowup surrounding the Great Depression. A 100% equity portfolio would have still been depleted after only 12 years. Even the 75% equity, 25% bond portfolio came dangerously close to a wipeout in month 238 when the $1,085,000 loan was covered by a 1,185,000 portfolio. In other words, your net worth was only $100k – down 90% relative to the $1m initial portfolio – and that tiny net worth was utterly insufficient to support a $1m+ margin loan. Another margin call blowup of the leverage strategy!

What about a smaller margin loan?

The lesson so far: fully funding your retirement through a margin loan and completely forgoing any withdrawals seems too risky. Then why not try to fund only a portion of your retirement through the loan and still perform some withdrawals from the portfolio to make up the shortfall?

Again, let’s start with a $1m initial portfolio, 75/25 allocation. Assume that we withdraw $20,000 p.a. (but with monthly withdrawals of $1,666.67 each). The remaining $1,666.67 per month comes from drawing on the margin loan. In the chart below I plot the portfolio value and the loan amounts. This time I include all three interest rate assumptions, 0.0%, 1.5%, and 3.0%.

Quite intriguingly, the loan will still get precariously close to the portfolio value. Sure, we scale down the loan by one-half, but now the portfolio time series is also lower than before because we’re withdrawing funds instead of using a buy-and-hold portfolio. At the same point as before, 201 months into retirement and at the bottom of the 1982 recession, the loan-to-portfolio ratios were 93%, 84%, and just under 72% for the three alternative interest rate assumptions. That would have likely triggered a margin call in all but the most optimistic 0.0% real margin interest assumption, which would have been a bit unrealistic anyway as mentioned above.

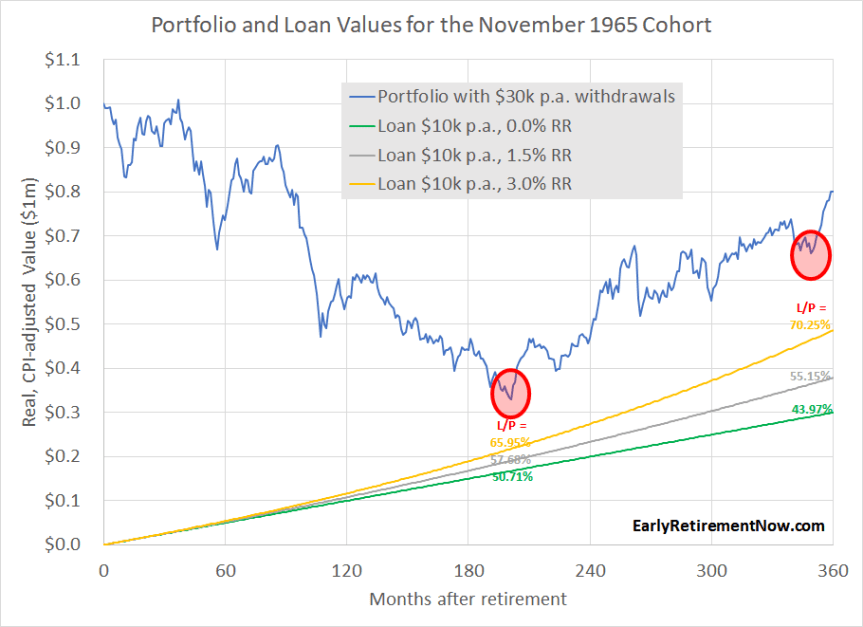

So, let’s take the leverage down another notch. Now we withdraw $30,000 p.a. from the portfolio and supplement it with $10,000 in annual draws from the margin loan. All done at a monthly frequency, i.e., $2,500 monthly portfolio withdrawals and $833.33 of monthly draws from the margin loan.

Now results look a little bit more palatable. Even with a 3% annual real interest rate, the loan to portfolio value always stays at 70% and below. Surprisingly, the largest margin utilization now occurs in 1994, right around the stock market volatility surrounding the Mexican Peso Crisis. With a 1.5% real margin interest rate you might have even stayed well below 60%.

But make no mistake: when your $1m initial portfolio is depleted by almost $700k after only 17 years and you also have a margin loan to service, this would have been a scary ride, because in 1982 nobody had any idea that the subsequent strong equity bull market would save your behind and the rest of your retirement. Recall the “The Death of Equities” Business Week cover from around that time and you be the judge if you had been comfortable with a $330,000 portfolio, a $200,000 margin loan, and $40,000 of annual withdrawals!?

Just for completeness, I also want to produce the same chart for the 3% plus 1% loan withdrawal strategy for the 1929 cohort. With similar results: The margin constraints seem OK, even when using the 3.0% real interest rate loan. Though, it must have been a tense retirement experience because the loan value would have come within just $200,000 of wiping out the portfolio.

Conclusion

If you’re a regular reader here on the ERN blog, you will notice that today’s material has a very similar flavor to my old classic post about the infamous blowup of an obscure derivatives trading firm in Florida: “The OptionSellers.com debacle: How to blow up your portfolio in five easy steps“. If they had been able to hold on to their portfolio of short natural gas futures options until expiration, they would have made a solid profit. But margin calls in between and the forced liquidation of all positions wiped out all customer accounts. And the same is true here: A strategy that may look attractive in the long-term could be subject to volatility along the way with catastrophic losses up to and including a complete wipeout of the portfolio. So, using excess leverage in retirement, specifically, funding most or even your entire retirement budget with a margin loan will likely exacerbate Sequence Risk if we were to have a repeat of the 1965-1982 asset return pattern. Unless you are so rich that, say, a ~1% initial draw rate is all you need to live comfortably. That leverage strategy works well for the 9-figure net worth households, but maybe not for us “lesser millionaires”!

But I have to concede this: If the margin loan is used very cautiously to merely supplement the withdrawal strategy we might have a winner here. It looks like a good point to start would be to target a 4% total spending rate, funded through a 3% withdrawal rate from the portfolio and another percentage point coming from a margin loan. Historically, that would have worked out extremely well. A 4% consumption rate would have never failed and you would have ended the 30-year retirement window with a very sold net worth number, even for the worst-case cohorts like 1929 and 1965. Possible improvements of this strategy would involve timing the margin loans, e.g., using the loan only after the portfolio drops below a certain level. I have that on my to-do list!

Thanks for stopping by today! Please leave your comments and suggestions below! Also, make sure you check out the other parts of the series, see here for a guide to the different parts so far!

Title Picture credit: pixabay.com

Well done, Karsten,

at least you made the 4% rule super safe by adding more risk (leverage) 😉

I’m longing very much for the application of dynamic rules (% from last market top or distance to moving averages). Probably, there is even more honey to suckle.

Liebe Gruesse Joerg

Well, sometimes a little bit of leverage can make things better. I have written about that: https://earlyretirementnow.com/2016/07/20/lower-risk-through-leverage/

I’m working on implementing momentum and valuation asset allocation strageis into the Google sheet. Hopefully in part 51. 🙂

Viele Gruesse!

This is a good article in the SWR series. What I would love to see: how a combination of different improvements in the withdrawal strategy would work together. You wrote in earlier articles e.g. about using gold in the portfolio to lower volatility. On first thought, I think this would really work well with the loan approach.

Basically, a retirement portfolio could be constructed from first principles including this new position of “increasingly negative cash”. It would be very interesting to see how the optimal portfolio (% of stocks, bonds, gold, loan) would have looked like for different retirement cohorts.

Yeah, good point. There are a gazillion of cases to consider. I might revisit some of the other methods and see how well they interact with leverage. 🙂

Yeah, I would love to see how this could be combined with the CAPE-based withdrawal strategy!

Thinking about that! 🙂

Ok second that!

I am glad you added those last two sentences. I was asking that ‘what if’ question the whole time I was reading.

Haha, I’m glad we’re on the same page! Will hopefully write about that next year! 🙂

Perhaps for a part 50 and beyond — what about in a “good sequence risk of returns” ending where after a retiree has planned for a normal 3-4% withdrawal rate, and thanks to great market returns their portfolio is growing, is leverage of any value in further improving their quality of life? And how to estimate that it is a good time to use leverage?

Aly,

Seems to me much more straightforward to handle that good SOR case by simply restarting the withdrawal amount to a higher number whenever the current portfolio is higher (inflation adjusted) than the starting portfolio. Kitces and others talk about this even when using a glidepath, so long as you reset the allocation amounts to their originals.

This independent of any use of leverage.

What ERN hinted at at the very end of his post was actually the opposite – that the optimum time to apply leverage is when the stock market is down. This is consistent with the principles behind the rising glidepath model that ERN’s already heartily endorsed.

Good response! 🙂

Thanks! Interesting suggestion. My suspicion is that if you have great returns early on and then a big blowup, You would have done better without leverage. Would have been better to withdraw from your assets directly while they were still expensive.

This again justifies doing something of an active and market-based leverage strategy: tapping the loan only when the assets down significantly. I will think about that and hopefully implement in a follow-up post! 🙂

A retiree in the higher tax brackets would not have to withdraw as much if they were using the margin loan strategy, because they would not owe as much in taxes, right?

That’s true. Of course, if you get a margin call and you have to liquadte all assets at once that would also be a bad tax scenario, but with modest leverage, you might have another advantage, as I mentioned in the intro: defer capital gains indefinitely or use the step-up-basis. 🙂

I’ve recommended margin as a ‘bridge’ for those who retired 5-10 years before Medicare & who are seeking to keep their mAGI low for maximum ACA subsidies since margin rates at IB are more attractive than for alternatives like a HELOC.

Yup, that’s a good application for using a margin loan: The subsidy cliff! Great point!

I feel like this is something that should be incorporated in the calculations, since it certainly will make a big difference in some situations! It depends a lot on what your tax rate is of course, but e.g. if you have a 20% capital gains tax on whatever you sell, the amount you withdraw as a loan can be as low as 80% of the amount you would have sold. Additionally, interest payments are often deductible (again, depending on where you live), which changes the math even more.

In some countries capital gains can be taxed as high as 42% (denmark seems to be the worst), so I would be curious if this is a more sane option in such cases.

I did mention in the original box spread loan post that the “interest” in the form of a S.1256 loss is deductible on your US tax return. Even though “normal” margin loan interest is often not deductible.

I’d love to see the same analysis but with a big mortgage. Why not take out a $1M mortgage at 3%. It’s not callable, so that problem is solved. The rate can’t rise, so that problem is solved. The only 2 issues are that it will be an amortizing loan and that the rate is higher than the current margin rates.

I thought about that. We bought our house for a bit more than 300k. Now it’s worth 500k. With an 80% LTV we’d get $400k from a mortgage, so it’s not really going to sustain us through a 30-year retirement.

Time to buy a bigger house.

Tell that to my wife! She wanted a small place: less maintenance. 🙂

Having used both a HELOC and a margin loan during accumulation phase, my experience is that psychologically having a loan that is not callable makes life much easier. This is one of the reasons why I am looking into rental properties for retirement income in addition to stock market – the option of tapping into the equity in the properties with a mortgage or HELOC during stock market downturn seems like a better option than margin loans.

I don’t think that a margin loan will ever be completely called. But the constraints might be tightened. Hence my preference for leaving a large cushion and not maxing out the margin loan.

HELOCs normally have a loan rates at or around 3% above the Fed Funds rate (Prime rate) or maybe Prime minus 0.50. That’s much more expensive than the FFR+0.5% to maybe FFR+1.0% with IB.

Big,

I got my SWR fix. 😎 Thank you. Truly a nice piece of work here.

Taking out a margin loan or mortgage makes you a debtor, and with the bond portfolio you are a creditor. One perspective — the debt is a type of negative bond (forgetting the duration differences) and you should rebalance the portfolio using the net creditor / debtor position.

For example, as the 1965 cohort (75% equity / 25% bond) approaches month 90, the net bond position goes negative and the equity position is now over 100%. At month 105, the portfolio is ~$600K ($450 equity / $150 bond) and margin loan is $400K yielding a net worth of $200K. The portfolio equity weight is 250% and net bond weight is -125%! I find this a bit extreme and more risky than the 100%/0% portfolio.

Your thoughts would be greatly appreciated.

^ This is an under-appreciated point. With an un-leveraged portfolio, when stocks fall, one’s AA becomes more bond-heavy. However, If you are holding a negative bond while stocks fall, your stock allocation actually goes up due to the shrinking denominator:

Example with an 800k portfolio:

Start with 80% stocks, 20% bonds, -20% margin. ($800k/$200k/$-200k)

Stocks fall 50%, bonds stay flat.

New AA is 100% stocks, 50% bonds, -50% margin ($400k/$200k/$-200k)

True. Of course, in my simulations, I assumed a fixed asset allocation with monthly reblancing in the S/B portion. 🙂

You last sentence resonated with my thinking … “improvements of this strategy would involve timing the margin loans, e.g., using the loan only after the portfolio drops below a certain level”. If I do any of this, it will probably be closer to this:

1) When markets go down, deplete cash/bonds from my existing 85%/15% equity/bons+cash to 100% equity first

2) Borrow on margin

Continuing my comment (posted before I finished)

3) Start to sell equities when CAPE ratios hit more normal levels to bring me back to my 85%/15% portfolio

Haven’t figure out specific CAPE ratios that will trigger when I change my portfolio balance but I’m gravitating towards using the CAPE metric to guide me directionally.

My plan is also similar. I am planning early FIRE at age 50 and plan to stay at 75/25 equity/fixed with 1) ~3.3% SWR with 1.7% from div/int yield and 1.8% from mix of margin + ( equity or bond sale)……

I always recommend consuming at least the dividends and interest because you already paid taxes on that (in a taxable account).

So, sounds like a good plan! 🙂

Phillip,

I agree with your plan in principle and in direction, but if you read ERN’s glidepath posts plus play around with his Google spreadsheet, 85% / 15% is too high an initial stock allocation, unless of course your withdrawal rate is sufficiently low.

ERN’s post and my playing around with his sheet show a 60%-65% initial stock weighting almost always allows a higher SWR.

I too plan something like your approach when the market is down, but the key is to reset to that 60%-65% equity weighting when equity markets are good, else you could get bitten by the SORR monster – which is the very thing the SWR series is designed to help you avoid.

Thanks! Good points! 🙂

Noted! 🙂

Thanks!

And that’s the other lever people might use before using leverage: sell the bond portion first (similar to glidepath) and then check how beaten down equities are. If they are, go to leverage.

It’s on my to-do list to write an update along those lines. 🙂

Really nice analysis. One thing I’d love to see is the effect of limiting the leverage to a specific level and if it reaches that point then start selling the portfolio rather than adding additional leverage.

Why do this? I feel like it could mitigate the sequence of return risk at the most crucial point for a retiree, i.e. when they switch from accummulation to drawdown. But should also reduce the risk of over leveraging yourself. It seems mad to let the leverage run wild, if you are hitting 70% LTV at any point I know I would be getting very scared.

So for example what would happen if you use only leverage for the first few years until you hit 20% – 30% loan to portfolio value which is gonna be 5+ years at 4% drawdown in a flat market, and then start selling your portfolio if needed. You could draw down more margin at a later point should the LTV drop below the threshold.

Paradoxically it feels like introduces a glide path by replacing the low risk bonds seen in a regular glide path with leverage which is higher risk than bonds. But no doubt when this is modelled out it turns out to be no good!

I guess the one obvious weakness to me is that this way of drawing down has you selling at the points where you portfolio would be at it’s lowest valuations and presumably this will have an adverse effect on the returns/risk of ruin.

I would use the opposite: delay leverage until you really need it, which could be 15+ years into retirement (for the 1965 cohort) and 3-5 years into retirement (for the 1929 cohort).

By using leverage first and then hitting the constraint when your portfolio is at the minimum you’d exacerbate Sequence Risk.

As always I enjoy all articles by Big Ern, but as always there are so many details…

As noted only the Taxable accounts will be eligible for margin, which is going to due with the exemptions in bankruptcy laws. States can differ along with the amounts, but the 401k, IRA, and possibly HSA will fully or partially be exempt (and likely part of the house will be exempt).

This is a big benefit to me as I would rather have protected assets in that rare event, and thus would draw down the Taxable accounts first.

In addition, I’ve slowly came to the conclusion to not have a mortgage in “early” retirement (and I enjoyed BigErn’s articles). This allows me to be poorer on paper and qualify for various programs (federal, state, and local) based on income, and all of these programs are hard to quantify a dollar amount as to how much they are worth.

(There might be some benefit of a “reverse” mortgage in “late” retirement, but I haven’t thought about it at this time.)

I like that approach. Not having a mortgage helps with Sequence Risk and has many other advantages, as you outline! And then maybe later in retirement you can still tap the equity as a last resort!

Yet another tool in the toolbox.

– start with 4% rule

– add SS later in life

– IRA to Roth conversions for tax arbitrage

– HSA

– optimize account w/d order

– margin, HELOC, portfolio secured loans to manage tax brackets and avoid tax cliffs

All this and more 😁

Good stuff.

Yes, good point! That could be another appeal of margin: live off the margin and avoid taxable gains to optimize the tax cliffs! Great idea! 🙂

I think I read that you have the margin loan always increasing, but I would be tempted to pay it off whenever the market reaches all time highs.

Very curious to see some optimized iterations where one is just using the margin to avoid selling anything for cash flow at below average prices.

Yes! I was thinking the same thing. Borrow when CAPE is low, pay it off when CAPE is high.

I have paid off my mortgage with anticipation that I would re-mortgage or sell/downsize when the market tanks to below average valuation, invest part of it and live off some of it until the market recovers. Mortgages are the cheapest (fixed rate) loans many of us can get.

Very true! The problem with a mortgage is that it’s really lumpy, multiple years of consumption budget. Do you want to put that big chunk back into the market? Might be good market timing, but would feel scary in real-time.

That’s the idea. But what if the new all-time-high takes too long?

But I get ya: I will research the active timing of the leverage portion. 🙂

I’m retired at 33 and thinking about using leverage if the market falls from peak by x%. Currently thinking x will be something between 33%-50% (or, start at 33% and increase leverage each additional 10%) but haven’t worked out the optimal amounts yet. I’d like to work this out while level-headed and not during a bear market – then just sit back and implement the plan if necessary.

Gotcha. Seems like a neat strategy.

Bravo. Very excited to see this article.

Can’t wait to read your follow up analysis on timing leverage.

That is conceptually how I am thinking of using leverage: only during the steepest market drops to avoid selling portfolio assets at a discount. Pay it off post recovery when I can I fund it with sales of non-discounted assets. The more rules based I can make it the better & your help is appreciated 🙂

Bonus points would be that interest rates are likely to decline post recessions making the leverage cheaper.

Thanks for all you do!

Thanks! Working on that!

Good point about the interest rate cyclicality!

1. Margin + Index Funds = Sometimes Risky

2. Margin + Hedging (Protective Puts) + Index Funds = Rarely Risky

3. Margin + Index + Hedging + Cash Flow Strats (SPY Options/Crypto Stablecoin Yields) = IMO safer/easier than Stock/bond mix

Yeah, that’s a good ranking. But keep in mind that the SPX options strategy already uses a lot of margin. Though, ideally, the SPX options trading will never fall much and you don’t even need additional margin. 🙂

I think the point with #2 would be to make the margin portfolio call-proof. I.e. if the long put means the portfolio cannot possibly fall below a certain point, maybe you engineer it so you can never be liquidated.

If the risk to watch out for in an unleveraged portfolio is running out of money, maybe the risk to watch out for in a leveraged portfolio is the margin call at the market bottom.

Re: #3, I’m not sure stable coins will be as stable as advertised for the next 20 years. Why add that layer of risk?

All good points. I can’t really be too sure on the stable coins+yield. The “stable” part might even persist, but yields might be lower in the future.

ERN,

Nice post. Most of it intuitive / consistent with your prior. But how do you square your conclusion (“If the margin loan is used very cautiously to merely supplement the withdrawal strategy we might have a winner here.”) with your multiple previous statements against a mortgage in retirement?

Not only is it non-callable, but you have the option in your favor so you can pretty much always ensure it’s not going to be more than 1.5% real, while there’s some chance it’s zero or even below zero.

Just because it’s true that mortgage rates are not as low as current margin rates, and that regular (non-IO) mortgages amortize, that doesn’t negate the benefits over plus parallels to the above. And your short answer above ($400K home equity loan wouldn’t sustain you) seems like a non-sequitur, since the idea is that it is only supposed to be a fraction of the “portfolio”

What am I missing?

Even at today’s low interest rates, a 30 year loan @2.75% still requires you to make payments of at a 4.9% nominal withdrawal rate which has failed for retirees who retired into the great depression and had some other stressful major drops (>65% real portfolio drop) during the 1910’s and 1970’s. Its not like other discretionary spending like travel and going out that you can cut during recessions until your portfolio recovers. Also, using investments to pay down your mortgage will also likely result in higher tax bills if the money is in a 401k or taxable account, thus increasing the failure rate even more. Additionally, many early retirees are planning on using ACA subsidies and using investments to pay down a mortgage will like result in a higher AGI, which could cost thousands a year in lost premium/cost sharing subsidies.

Good point! Even with the interest rate so low you have to make a large principal paydown, hence the 4.9% implicit (nominal) withdrawal rate.

But: If one could time the bottom of the market and take out a mortgage to partially pay off the existing margin loan it might not be a bad option.

I agree if it was possible to be able to take out a low cost 30 year fixed rate mortgage anytime stocks were down 30%, it would be a great option to avoid selling stocks low, but mortgage companies are stingy about giving out mortgages to people who are living off investments, especially during recessions.

Yup, that’s a big concern! Banks might become stingy at that point. Even though the interest rate might be very low due to Fed policy.

Due respect, while the point about ACA subsidies (and Medicare costs) is quite legitimate for people in income brackets where that is an issue, the rest of your argument doesn’t hold up since you confuse nominal withdrawal rate *percentage* and don’t seem to consider the fact that you now have a much higher amount of money per year.

Arguing that you need to have 100% of your home value in home equity for years 1 – whenever, rather than having it go from 20% to 100% over 30 years, is financially nonsensical (modulo the mortgage interest rate cost). The whole point of the article re the advantage of leverage is having the larger amount of money to use as a cushion. By definition you don’t have any of that home equity being used as an annual spending cushion when equities are down if it is already tied up in home equity! Similarly if taxable 401k/IRA money was at issue, how would the mortgage have been paid off in the first place?

The mortgage in advance (and I agree an IO mortgage would be superior if available) has the major advantage of being non-callable, and as multiple people have pointed out getting a loan is more difficult when markets are down substantially. And you have the optionality in your favor (refi but can’t be called).

Obviously rates matter, but interests rates are very low now. And less obviously to some but no less true, it still makes relatively little sense to hold a big mortgage while having other money invested in bonds if they are paying a lower nominal interest rate than the mortgage, because then you have created a very expensive option. But the leverage in retirement logic underlying the rest of ERN’s post remains.

I didn’t confuse nominal and real which is why I deliberately specified nominal in my reply. There have been non zero failure rates for a 4.9% nominal starting withdrawal rates historically, and that doesn’t even include all the other tax consequences of carrying the mortgage. As I stated later in the reply, if they let you take out a mortgage for no cost anytime in retirement when it was advantageous say when stocks are down 30%+, it would be a great option but the fact that you can’t and have to start paying down principal year 1 makes it undesirable for most early retirees.

Even ignoring ACA subsidies, (which happens to save thousands per year for the majority of early retirees), there are other tax considerations that you may be running into by having a higher AGI due to using investment gains/income to pay a mortgage such as the 15% dividend/capital gains bracket, higher ordinary income bracket, higher EFC on the FAFSA for those with kids in college, loss of saver’s credit or EITC for those who continue to do part time work in retirement, higher medicare premiums once you get to age 65. In our marginal income tax bracket system, it really pays to have as low of AGI on paper tax wise as these all these additional taxes can add up to thousands of dollars per year, not to mention additional headaches and complexities to your life in retirement. Just like anything, there might be a very small sliver of the population that these tax credits don’t apply to but for most retirees, a mortgage isn’t worth it even at low interest rates.

FIGUY,

You are making two completely different arguments.

In your second paragraph, just as in your initial comment, I do indeed accept that the AGI/subsidies/Medicare/marginal tax rate reasons may *by themselves* be sufficiently good reason for many – heck, even most – people to payoff the mortgage and go that route. Almost independent of mortgage rates, and certainly for the rates available today in the context of keeping a large chunk of your portfolio in intermediate government bonds.

But your first paragraph’s first two sentences, where you reiterate the relevance of “4.9% nominal rate”, is where you have it wrong. First, because as stated it ignores the fact that you have very different portfolio values in the case of having a mortgage or not; the money for that mortgage payoff had to come from somewhere (or the money form taking out a mortgage now substantially increases your portfolio). And so then it becomes a question of what the interest rate on the mortgage is. To use just one somewhat realistic possibility, if the mortgage rate is 2.5% nominal, and in a couple years real interest rates got to 3% while inflation is 3.5% (so 6.5% nominal interest rates), you will obviously be better off with that long term mortgage, no matter what your portfolio composition is, and regardless of the fact that you must “pay back” some of that mortgage principal each year.

In real life of constructed scenarios, whether in hindsight or not, I fully acknowledge that it becomes the combination of both sides of this “argument” that matters, and it could well be that the lower AGI wins out. But especially in the context in which ERN’s post was written (using leverage…), the 4.9% nominal so-called failure rate is not the problem.

Yes in your very specific unrealistic scenario where you had perfect timing and held off investing it in bonds since they decrease in value as interest rates rise then waited to buy them after interest rates went up to more than you borrowed at then obviously you would benefit by not having a mortgage but feel free to plug in a 4.9% nominal withdrawal rate into ERN or your favorite back testing site and you will find that historically it isn’t a safe withdrawal rate.

All of the tax arguments are just further evidence on why it doesn’t make much sense in practice in most cases.

Yes I know there have been many times where having was successful just like 5%+ withdrawal rates have often been successful, my point is leaving money that you could payoff your mortgage in investments it isn’t always successful all of the time and just not worth all the added stress for when the market is down 30%+ and tax complexity.

Well, in fact just now I used ERN’s 2.0 spreadsheet and it shows that using a 4.9% nominal initial withdrawal rate, *and* increasing the withdrawal yearly with inflation (which of course is *not* necessary for a fixed mortgage!!!) works since 1926 100% of the time for all inflation rates higher than 1.5%.

[And note: Using a portfolio of 60% stocks, 27% bonds, 13% gold – as ERN suggested in Part 34 (Gold as a Hedge against Sequence Risk…) yields still better results]

While ERN’s sheet does not do/show the calculation, I’m very comfortable asserting that given that with a fixed mortgage the withdrawal amount in fact DOES *NOT* INCREASE at all each year, such a withdrawal rate since 1926 would have worked for all inflation rates higher than ~0.5%, even with a 50-50 portfolio

And none of the above considers the likely incremental improvements in mitigating SORR where you leave most or all of that “mortgage” money as initial cash cushion and “glide path” it into stocks only after stocks have gone down.

You continue to have your argument backwards. The AGI / tax / subsidy points *are* the reason why it’s generally the case that not having the mortgage is a better idea most of the time for most people. They are not, however, “further evidence” of a false 4.9% nominal withdrawal rate failure assertion.

Given current nominal interest rates, mortgage rates and inflation (thanks to current Fed policies that are clearly unsustainable – ERN has suggested as much in recent posts), and likely possibilities of medium term inflation, I submit that rather than being an “unrealistic scenario” now is precisely the time to consider a low fixed rate, non-callable – but with optionality to refi or pay off at your discretion – mortgage as leverage in retirement.

The only problem with doing with adjustments for inflation is that in the 1930’s there was DEFLATION. It took 14 years for prices to get back to where they were in 1929, so the deflation adjustments in ERN’s tool all made all your other withdrawals go down but a 30 year loan payment stays the fixed in this situation.

The debt is callable in the sense that they require you to make principal payments every single month for 30 years where other types of debt like margin interest doesn’t. I prefer margin interest because you can selectively use it only when its advantageous such as when stocks are down 30% to avoid selling low and you don’t have to take it out and pay interest when you don’t.

Also, the other problem with back-testing using today’s interest rates that I’ve mentioned earlier is you couldn’t have borrowed at <3% rates (even the government couldn't) at those times to mitigate SORR so using a rate is also unrealistic as well.

CPI dropped 27% from 1929 to 1933, so withdrawals for your inflation tied expenses dropped but fixed ones like a mortgage didn’t. If you modify the CPI in the worksheet to be constant from 1929-1958 like a 30 year mortgage withdrawal would be, the SWR since 1926 falls to 3.3%!

Side note, 1933 it was a federal felony to trade gold so you couldn’t just say you’d use it to survive the great depression. Instead, you’d have to withdraw more from you equities which were down 80% to make your mortgage payments in 1933. Ouch!

In that case, having a mortgage would have been a retirement killer. Very true!

FIGUY, you’re 100% correct that given sustained deflation, you don’t want a mortgage (even with the ability to refi the rate downwards as interest rates collapse).

That said, while none of us know exactly what will happen in the future, one thing I am quite sure of is that the “Helicopter Ben” Fed will never again allow sustained deflation. And I’m someone who is not a big fan of the Fed the last 25 years. But they know a) that they need to prevent deflation, and b) how to do so.

But if you want to protect yourself against deflation, go right ahead. I concede that it is the one – and essentially only – case where your “4.9% nominal withdrawal rate causes failure” claim has validity

Good point. I assume that the interest for the margin loan is borrowed again from the margin loan.

In contrast, the mortgage has a fixed nominal cash flow that increases your withdrawals, hence my preference for paying off the mortgage.

But you’re right: the mortgage has some appeal, incl. the refi option if rates go down and the fixed rate feature in case rates go up.

Maybe consider a rising glidepath that goes from 60/40 -> 100/0 -> beyond?

Yes! See parts 19+20! 🙂

What about using a HELOC instead of an amortizing mortgage? Use it as your ‘withdrawal’ bucket during 10%+ downturns or similar and pay it back in installments (as a portfolio withdrawal) once market recovers to previous highs.

HELOCs usually have loan rates Fed Funds Rate +3.0%, Maybe +2.50%. Too expensive.

And: HELOCs can also be called.

Anything beyond 60/40 is (and should be) too risky for most people!

Blanket statements like that are not useful.

Bonds are risky, too. They don’t keep up with inflation right now. You have less risk of volatility short-term, but higher risk long-term of running out of money.

I agree with you ERN. portfoliocharts.com still puts a PWR of 3.5 in a 60/40 portfolio. Can I trust that?

Over a 30-year horizon, that seems to be a save WR, yes.

Its interesting that once you go above 30% bonds in your portfolio, the high inflation/falling bonds of the 1960’s/70’s becomes and even worst case scenario for retirees than the great depression.

Dammit I know….I don’t want to gamble in the stock market and loose sleep but I still want to FIRE.

What should I dooooooo???? If possible I want to have ZERO in stocks!

I personally don’t really think of investing in diversified index funds as gambling. What is your chief concern?

Its only a gamble if you’re frequently moving large amounts of your portfolio in and out of the stock market at once. If you’re just periodically buying equities as you earn it holding for long term then periodically selling small amounts as you need for spending in retirement historically you’d do pretty well even with lots of volatility along the path to retirement.

Tell that to my brain. I buy today, if the market goes down half a % I place a sale order tonight to execute tomorrow…this is how I am, I can’t help myself. I tried but I just can’t see my money going down and I know it’s psychological ! urh! why investing has to suck so much for people like me. Fear just paralises me, period.

Some people who have a hard time with that do well with target date retirement funds. They feel more comfortable when its Vanguard pulling the strings on asset allocations. Just tell yourself that “I’m only a buyer of this fund until my target date when I have the cash then in retirement I’m only a seller when I really need the cash”.

Maybe try real estate then?

Correct! 75/25 is about the balance between 1929 and 1965. More bonds, then 1929 looks better and 1965 looks worse. And vice versa! 🙂

If you believe – as I do – that the one thing the fed can definitely prevent is sustained deflation (see the famous “Helicopter Ben” statement), then ERN’s Google sheet shows that since 1950, the right amount of bonds is zero, and an allocation of 65% equities, 35% gold delivers the highest SWR.

Even if one is not willing to go that far, still makes far more sense to optimize for 1965 case than the 1929 one.

Personally I intend to use fixed annuities (and probably mostly DIAs) for the “bond” portion of my total portfolio in retirement, other than a small cash “bucket”/cushion

Well, 35% gold seems a bit high. But 10-15% seems to be a good hedge.

What kind of annuity yields do you get these days?

Well, I’m planning to buy DIAs that start at age 70, primarily as longevity protection as a supplement to Social Security. And of course payouts vary greatly with age, due to the value of the mortality credits.

I use incomesolutions.com for quotes. As of today, for a 57 year old male, the payout “yield” is ~4.87%. For a 40 year old male, it’s ~3.79%

Both numbers substantially lower if you want a (fixed) COLA, and no one currently offers a COLA based on actual inflation.

I believe there is an even better methodology than a margin loan to finance this strategy. That would be selling a box spread. You achieve extremely low interest rates (typically better than IBKR, TDA, etc.). You also don’t have risk that during market turmoil the broker could call the loan early. You are limited by the longest available duration option chain on SPX, which is just over 1400 days. I calculated a 1.1% annualized interest rate on a $200K loan using the 747 DTE SPX chain, if filled at mid.

Interesting. I tried to price a box spread on IB but over the weekend there’s no quote. Have to check again on Monday and see what kind of implicit rates I would get.

Hi Tim,

What exactly is “box spread” what is the setup?

Pick two strikes close the underlying, e.g., S&P at around 4600. For example 4500 and 4700.

Sell a Call at 4500, buy a call at 4700

Sell a Put at 4700, buy a put at 4500

This would guarantee you to pay out $200 at expiration. No matter where the underlying ends. With a multiplier 100x that would be $20,000.

You have now effectively issued a zero-coupon bond paying off $20,000 at a future date. Try to do this ~3 years in the future, e.g., with the December 2024 SPX options.

If you can sell this spread and maybe get $20,000 minus x then you got a loan at a potentially very competitive interest rate. That’s because a non-arbitrage condition should exist and price this at about $20,000*(1-risk-free interest times the number of years).

Thank you Karsten.

A couple quick notes/warnings to add:

1. You have to do this setup using european style options (like SPX) and not american style (like SPY). Otherwise, your deep ITM short options are at risk of early exercise, which could be very disruptive to your portfolio.

2. This doesn’t prevent you from being vulnerable to a margin call during a downturn, just like with a margin loan. You effectively are loaned the money at low interest, but your brokerage account buying power and margin equity doesn’t change. When you withdrawal the cash to fund your retirement bills, you will reduce the margin equity in your account. Just means that you need to be cognizant of your portfolio during drawdowns to avoid margin call, same as with a margin loan.

3. You need Portfolio Margin enabled and full options approval with your brokerage to utilize this strategy. This is all done from a taxable, non-IRA style account.

Yes, all good points!

1: I’d use the CBOE SPX options.

2: I would do this in moderation, that’s for sure. So far I haven’t been able to get any of my limit orders executed.

3: Noted. I’ve been using portfolio margin for the longest time! 🙂

You may have to move a point or two below mid—walk it down 5 or 10 cents at a time. I’ve always gotten decent fills, generally locking in rates around 0.75% a year (slightly higher recently) on two-year options.

The correct site is https://www.boxtrades.com/ – it has a neat graph that shows what rates box spreads have traded at recently.

And here’s the thread that inspired it – https://www.bogleheads.org/forum/viewtopic.php?f=10&t=344667

Got it. Thanks!

I think they’re including commissions in the APR calculations–would that explain the discrepancy between your numbers and theirs?

I suspected that, too. But even with commissions I only get 1.67%. Not the 1.73% they calculate. Strange…

Well, 0.68% is the current 2Y Treasury yield. If you could get 0.75% that would be an awesome APY. But I guess it’s now higher, around 1.00%? I heard that 30bps is “fair” srpread.

It looks like 2-year boxes are going for 1.10% – 1.20% APR right now (per boxtrades.com).

Personally I’m happy with anything under 50bps spread. I prefer to walk my price down quickly and get a fill in <15 minutes, rather than wait a week to potentially save 10-20bps. I also suspect spreads may generally be higher on the 5-year options you're looking at, as there's less liquidity that far out.

OK, that makes more sense. That’s a 40-50bps spread,

I like the site. I can even see my trade on 12/6: It’s the Dec 2026 trade, 4600-4400 spread.

One complaint: The implied interest rates seem to be incorrect. It’s not 1.73% but 1.67%. Not sure how they can mess up that calculation. (20000/18400)^(1/5.03)=0.0167.

There’s one other potential benefit of the box spread over a margin loan, depending on your tax situation: the box spread “interest” is considered a capital loss, so all the interest paid can be used to offset capital gains. Whereas with a margin loan you would need to itemize deductions in order to deduct the interest.

Correct. Stay tuned for the tomorrow’s post on box spreads. I will mention that point! 🙂

I think this is very helpful.

There’s a good thread on bogleheads on box spreads for those interested in learning about them. The thread even spawned a website called boxspreads.com

Nice. Thanks for the link. I wrote my first box spread trade today.

Will likely write a post about the mechanics later this week or next week.

What’s your take having written one now? I have not personally written one (I don’t have a need yet), but am considering it as a tool in the tool box.

Writing the post right now. Looks not too shabby. I got a little bit impatient and bid up the interest a little too high. I got 1.6% for a 5-year loan. Not bad considering that the Fed Funds Rate will likely march toward 2.5% again over that time span.

Should have waited longer and see if I could have gotten 1.5% which would have been the prevailing 5-year Treasury yield plus 0.30 at that time.

Do you think it would be feasible to simulate this strategy somehow with leveraged ETFs? The rates are significantly lower, for example SSO gives 2x leverage at an expense ratio of .89%. I also don’t really want to transfer to Interactive Brokers haha.

Not recommended.

First, you don’t compare the margin rates with the ETF expense ratios. That’s comparing apples and oranges.

Second, over time you’d have to replace your entire equity portfolio with ETFs. You’d liquidate all your capital gains. With a huge tax bill.

It’s indeed most efficient to leave your assets untouched and use a margin loan.

If not the expense ratio, how should we compare the interest costs of leveraged ETFs to loans?

Liquidating capital gains won’t be an issue in my case as long as it’s over time, since I only plan to withdraw 25k-35k per year I’ll be well within the zero bracket for capital gains.

It’s a great question, by the way. I might add another section in the main article to address this issue.

We have to compare the expense ratio with the Loan spread over the risk-free rate not the entire loan rate. That’s because a leveraged ETF doesn’t give you exactly 2x the underlying but 2x the underlying minus the risk-free rate.

With an E.R. of 0.89% you’re already in the same ballpark as the IB loan spread, Once you factor in transaction costs plus the fact that leveraged ETFs always perform really poorly if there’s a lot of volatility because they get whipsawed, I would stay away from those leveraged ETFs.

But it’s a good point. I will certainly research this some more. 🙂

One advantage of leveraged ETFs is the lack of margin calls during crashes. As long as the ETF does what its supposed to do and you can hold it during crashes does it matter if it doesn’t return exactly 2x or 3x the SP500? I have UPRO in my IRA so I can easily manipulated my overall leverage level without incurring cap gains.

Good point. But it comes at the cost of the higher expense ratio and the trading costs.

See the post https://earlyretirementnow.com/2021/12/09/low-cost-leverage-box-spread/ toward the end where I show that some of the leveraged ETFs underperformed the “theoretical” target by 10+% per year.

More details.

https://www.portfoliovisualizer.com/backtest-portfolio?s=y&timePeriod=2&startYear=1985&firstMonth=1&endYear=2021&lastMonth=12&calendarAligned=true&includeYTD=false&initialAmount=10000&annualOperation=0&annualAdjustment=0&inflationAdjusted=true&annualPercentage=0.0&frequency=4&rebalanceType=4&absoluteDeviation=5.0&relativeDeviation=25.0&leverageType=0&leverageRatio=0.0&debtAmount=0&debtInterest=0.0&maintenanceMargin=25.0&leveragedBenchmark=false&reinvestDividends=true&showYield=false&showFactors=false&factorModel=3&portfolioNames=false&portfolioName1=Portfolio+1&portfolioName2=Portfolio+2&portfolioName3=Portfolio+3&symbol1=SSO&allocation1_1=100

Check out the Metrics tab. You have a beta of 1.97. That’s good, almost exactly 2x leverage.

But check out the alpha: -3.61%. So, you’re lagging behind the true 2x S&P 500 by 3.61%. That’s much higher than just the expense ratio. Other factors like daily rebalancing of futures contracts, and getting whipsawed during high-vol periods enter here.

Not recommended at all!!!

Perhaps another cash flow option for people who are between 62 and 70 when a recession hits would be to start SS early so they don’t have to withdraw as much from their portfolio. Would probably need to run some simulations to see if it actually helps in the long run.

Or: use leverage to bridge the gap and get the max benefits at age 70. Especially when there is a spousal joint benefit consideration.

Definitely. Lots of options to consider.

The major downside to starting SS early is that you’re far less protected from longevity risk. The single best thing by far you can do for that is delay taking SS to 70. Yet another reason why ERN’s suggestion to use leverage to bridge the gap is preferable

How about a short term scenario? Retired, $10,000 of dividends. no other income. Four years to SS, 6 years to RMDs. When this time comes we have more income than needed. So I live off margin for four years, reduce the margin draw by the SS amount when SS starts, then when RMDs start, use excess money to pay down the margin.

My reason for looking at this is so I can maximize my Roth Conversions. Yes, I will be paying taxes on the Conversions, but I can convert more because I don’t need to use any of the IRA for spending.

As it stands, IRAs have been growing faster than I can convert them. (ya, a good problem to have, but still, it creates a tax problem)

I think that’s a splendid use for margin. Because of the shorter horizon, only 6 years, there is much less uncertainty about hitting the margin constraint, like in the 1965 cohort getting messed up decades into their retirement! 🙂

You should also try the rising equity glidepath simulations with negative bond weights, if you have access to such good rates on short bond positions.

The other simulation you should try is just withdrawing a fixed percentage of your stock portfolio each year, then the difference between the proceeds and your desired retirement income is borrowed or paid back from the loan balance

I like that idea. You’d use the leverage only during the relly large drops. Have to think about how to simulate this. 🙂

This sounded really nice to me too, so I made a quick hack of the toolbox “Case Study” tab to test it out. https://docs.google.com/spreadsheets/d/1u928Cxab76EEUdVNbO36hDIb9IppRFvfDXbvFuo99gM/edit?usp=sharing

Assuming I’ve set up the spreadsheet calculations correctly, it seems to be at most a modest improvement over the 3% withdrawal 1% loan strategy in terms of avoiding margin calls that wipe you out. It does however have a massive improvement in the final net worth after 30 years – September 1929 ends up with almost exactly $1 million and November 1965 ends up with about $750k. For early retirees I think I can strongly recommend this!

Not sure how exactly you “hacked” the sheet to do this. But the result sounds about right! 😉

I was thinking about the same thing. A combination of the 2 extremes: fixed percentage withdrawal vs fixed dollar withdrawal using leverage. I wonder if this could allow you to maintain a larger proportion, if not all your portfolio in equities, and let the leverage even out your spending.

All good suggestions. Thinking about how to implement! 🙂

Yes, a 100% equity portfolio plus leverage feels like a rising GP. But there are some differences. THe bond returns I use are the 10Y benchmark bond, i.e., constantly rolling into the current 10Y bond. On the other hand, the loans have interest rates tied to short-term rates or fixed term rates (an in the case of the box spread)..

I would be interested to see how a portfolio with a set percentage margin loan faired. It would counterintuitively require selling stocks when they go down and buying more when they go up to keep the margin loan at say 25%, but could keep the portfolio from getting wiped out in a downturn. The book Lifecycle Investing advocated for something like this but not in the context of early retirement.

Haven’t simulated that yet. On my to-do list. 🙂

Thanks!

Surprise no one mentioned Wade Pfau, he wrote books on funding retirement with borrowed money, more thru the lens of reverse mortgages but he does mentions margin loans as well. There are 3 studies done on this topic with different rules for withdrawal which will certainly be interesting to see ERN’s POV with the margin loans

Haven’t seen the Pfau article. Link?

I personally hate the reverse mortgage because of the excessive fees and high rates. That’s probably the worst kind of leverage you want to use.

This is a great point. I see on TikTok that a lot of folks talk about ‘borrow til you die’ but they neglect to talk about margin calls during bad times.

But it seems like if one could convert $1m->$3m then you could perhaps convert that money into an all-cash real estate transaction and mortgage that up at a low rate. $QYLD that borrowed money or something and then make a dividend spread on it with less volatility. You can’t get called since your loan’s on your house, but you might lose your house if dividends stop for a long time and you have no other savings.

Yes, that’s the whole point. A good strategy for Warren Buffett, Jeff Bezos, etc.

For normal mortals, it’s unlikely that you can fund all your retirement like this! 🙂

Hey Big Ern,

What do you think about taking out a loan during a large market dip, to cover living expenses. Then paying it off when the market rebounds, and resuming normal withdrawels?

That’s what this post is about. As I outlined in the post, if the dip is deep enough and long enough it could wipe out you entire portfolio faster than the good-old 4% Rule.

I think recent events have shown just how scary the implementation of this strategy can be – I would be sweating a ton right now if I were pulling my living expenses from a margin loan, with a variable rate tied to a federal rate that has been forecasted to increase greatly in the next couple years, against a dropping portfolio. Mathematically it may work, but it’s important to evaluate just how stressful a strategy is. I’d love a comparison of the SWR generated by a 1%/3% vs 1.5%/2.5% 2%/2% margin/withdrawal rate, compared to the SWR’s generated by things like bond tents.

I believe this would be an excellent addition to the ERN series – a formal measurement I will deem the “b*tthole clench factor”, meaning just how close a withdrawal strategy comes to total disaster even if it succeeds in the long run.

Haha, I’d have to finbd a name for it. But yes, the intra-month volatility, maybe even the intra-day volatility would need to be measured to see how close you come to getting wiped out.

Might not be worth the “angst”.

But I like the option to use leverage to bridge short-term cash flow needs. It can never replace actually selling some of your assets in retirement! Unless you’re in the 9-figure or 10-figure club!

I agree that this would be an excellent idea. But note that even bond tents (a.k.a. Glidepaths) have sleep-at-night issues of their own.

The 40% —> 100% or 60% —> 100% glidepaths that ERN demonstrated work best at improving SWRs if adhered to programmatically mean that you will have 100% equities for your entire retirement after 10 years.

I don’t think most people could – or even should! – do this.

I’m pretty confident I could hold about 90% in stocks if the stock market fell 40%, but not sure I’d feel comfortable all the way at 100% even in that case, and quite sure I wouldn’t feel comfortable with 100% equities if the stock market is at a new high.

What do you think now that fed funds rate is 5.33% and even the lowest margin rate at IBKR is between 6-6.3%?

While borrowing costs more, it seems the potential cost of withdrawing could be more if the portfolio hasn’t recovered from a downturn and the loan would have to be repaid from asset sales?

Please see the other post on the topic.

Ah nevermind, I just read the post on timing leverage and the analysis with FFR+x% makes a lot more sense! Great follow up post!

Ah, there you go. Glad you found it! 🙂