March 16, 2023 – After the tumultuous year 2022, it looked like 2023 was off to a great start. But banks threw a monkey wrench into the machine, with the S&P almost erasing the impressive YTD gains, several bank failures, and the prospect of a worldwide banking crisis that all changed. So folks contacted me and asked me if I could weigh in on this and some other issues.

Here are some of my musings about bank failures, government failures, moral hazard, and why the FDIC should eliminate the $250k limit and simply insure all deposits…

Bank Runs in Practice: The Silicon Valley Bank Failure

My blogging buddy Mr. Shirts wrote an excellent post-mortem about the stunning Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) failure, and I highly recommend you check out his post. In a nutshell:

- SVB experienced large inflows of deposits over the past few years. Most of the deposits exceeded the $250k FDIC-insured limit. That’s because many depositors were startups who received sizable cash injections from VC firms and needed to store that money somewhere “safe,” like a checking account at SVB.

- SVB wasn’t heavily involved in the traditional bank business like loans and mortgages. Startups don’t usually get traditional bank loans. So, to make money off all those deposits, SVB invested a large chunk of its assets in interest-bearing assets, like Treasury bonds, Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS), etc. All very safe instruments with essentially zero credit risk.

- The asset portfolio was heavily biased toward longer-maturity bonds to earn more interest income. As you all recall, bonds went through a brutal bear market last year after the Federal Reserve moved up short-term rates from zero to almost 5% at the beginning of 2023, taking all longer-maturity bond yields with it for the ride. SVB learned painfully that Treasury bonds might not have credit risk, but the duration risk can be just as bad!

- With a balance sheet underwater and many fickle depositors worried about losing their uninsured deposits above the $250k limit, a bank run ensued. Customers were lined up outside their branches and wrapped around the block, invoking unpleasant memories of the 1930s. But of course, the death blow came from $42b of electronic withdrawals, nicely coordinated by the Silicon Valley VC community. With friends like these, who needs enemies?

Businesses fail all the time. A bank is a business, too, so what’s the big deal about a bank failure, then? Simple: investors now wonder how many more SVBs are out there. That’s a unique feature of the financial sector. In contrast, if you run a sandwich shop and one of your competitors goes out of business, you might even celebrate; less competition likely means more profit for you.

But in the banking sector, three bank failures in less than a week will put the entire industry under scrutiny. Everybody is guilty by association. Sometimes, even healthy banks can fail during a coordinated bank run. It would be mightily unpleasant if a bank failure in California or New York drags down the entire world banking system. As much as I am a free-market capitalist in many other aspects, there are reasons for the government to step in and assist the banking system because of systemic contagion risk.

How can healthy banks get sucked into a crisis? This brings me to the next item…

Bank Runs in Theory: The Diamond-Dybvig Model

The Diamond-Dybvig Bank Run model was published in 1983 (“Bank runs, deposit insurance, and liquidity.” Journal of Political Economy. 91 (3): pp. 401–419). Intriguingly and in an outright creepy coincidence, Professors Diamond and Dybvig received the Nobel Prize in Economics in late 2022 for this work, alongside famous macroeconomist and former Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke for his (separate) academic work in understanding financial crises. You can’t make this up; maybe the folks at the Sveriges Riksbank knew more about the coming chaos in 2023 than our U.S. regulators, but I’m not into conspiracy theories.

In any case, in a Diamond-Dybvig model (DDM), you could have a completely healthy bank with sufficient assets relative to its deposits. However, suppose all depositors, in a coordinated attack, wanted to withdraw all their deposits. In that case, the bank might not get a fair market price for all assets and must now liquidate assets at “firesale” prices. The proceeds may now fall short of satisfying all depositors.

In essence, the model creates two equilibria. If the other customers don’t withdraw their funds, I have no incentive to do so either, and the bank keeps operating as usual. On the other hand, if a critical mass of depositors withdraws money, then I don’t want to be last in line and left holding the bag. Thus, whether I need the money or not, I participate in the run, too.

So, even a perfectly healthy bank could fail in this unpleasant equilibrium. Also, the failure has nothing to do with Moral Hazard. It’s a self-fulfilling prophecy that takes down an otherwise healthy bank. As a policy recommendation, Professors Diamond and Dybvig pointed out that deposit insurance can improve outcomes and break the vicious cycle of a bank run. Note that the absence of deposit insurance can cause a bank run. And deposit insurance can prevent a bank run. It’s the opposite of moral hazard!

But for the record: SVB was not healthy!

The difference between SVB and the bank in a Diamond-Dybvig model is that SVB was unhealthy. It was underwater, not because illiquid assets needed to be liquidated at firesale prices. Treasury bonds trade in a very liquid market, and bond prices were down not because of a firesale but because the Fed raised short-term rates, shifting the entire yield curve as well. Thus, SVB was insolvent even at fair and competitive market prices, not just firesale prices. Worse, SVB was mathematically insolvent before the bank run even began! It wasn’t a multiple-equilibrium problem. There was only one single equilibrium, and that’s called “SVB is toast!”

You may ask, don’t we have regulators? How did this go undetected? This brings me to the next point…

Regulators failed!

If SVB had regularly valued its assets at market prices, a process called mark-to-market, the hole in the balance sheet would have been apparent very quickly. However, SVB used an accounting trick to hide this hole. A bank can keep two buckets of assets: assets available for sale (AFS) must be marked to market. Assets the bank intends to hold to maturity (HTM) don’t have to be written down in response to price drops. The logic behind this is that, for example, during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC), many banks feared having to write down their loan and mortgage portfolios. Nobody wanted to touch those assets, and the market priced them at steep discounts. So, on paper, a bank may look insolvent, but only when applying fire-sale-like prices. In contrast, those assets could have likely paid off if held to maturity. But this two-bucket approach helped avoid the effects of dramatic price drops of highly illiquid assets, not the market repricing of highly liquid Treasury bonds.

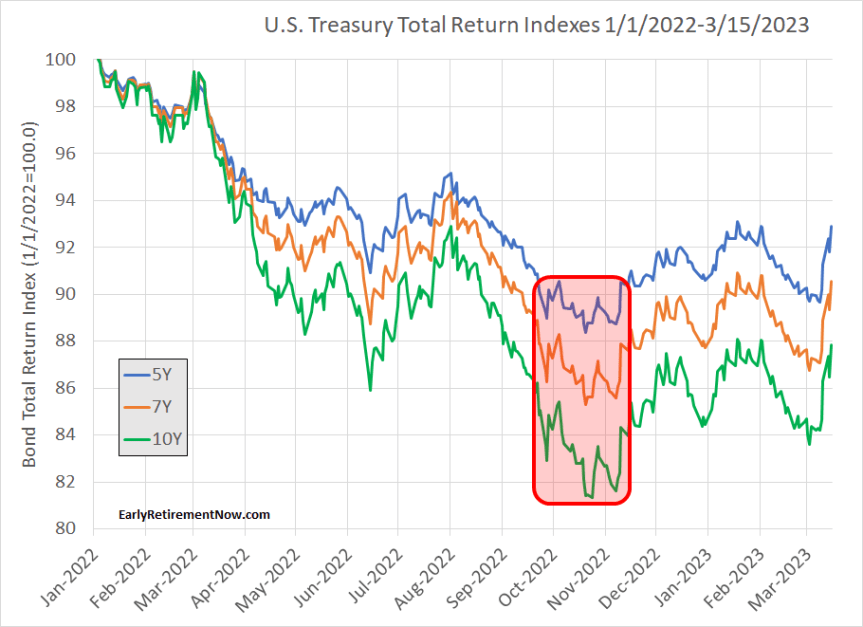

This begs the question, why didn’t banking regulators catch up to this? It’s not like bond yields just recently rallied. Indeed, U.S. Treasury yields in early March 2023 were still well below their October 2022 peaks. If SVB was insolvent on March 10, it should have been in even worse shape between late September and early November 2022. As you can see in the chart below, Treasury total return indexes have since recovered a little bit. If this is all due to a duration effect, why didn’t the CA State regulator and Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco act six months ago? Why wait for so long to attempt to recapitalize SVB? The risk managers at SVB and the “experts” at the relevant government regulatory agencies must have been asleep!

Moral Hazard

One widespread myth is that banking crises result from Moral Hazard because reckless bankers played a game of HIWTTGBMO – “Heads I win, tails the government bails me out.” I find that story very unconvincing. Not just because the Diamond-Dybvig model generates bank runs without any moral hazard. But also because I’ve worked in finance all my life. Between 2008 and 2018, while working in asset management at BNY Mellon, I operated under the principle “If I do well, I get paid well. If I screw up, I lose my job, reputation, CFA charter, and money, and depending on the severity of the screw-up, I might be banned for life from working in the securities industry again.” I always felt those incentives were pretty well aligned with what’s best for the banking world and society at large.

The closest I came to HIWTTGBMO was during my time at the Federal Reserve: “Heads, I get a government salary and benefits, Tails I get a government salary and benefits.” Of course, I worked in economic research without any potential to cause harm to the real economy, but I’m sure that the bank examiners at the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation and the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco that were asleep at the wheel will keep their jobs and pensions and will keep operating as usual after this. If people are looking for a Moral Hazard problem to solve, maybe start with the regulators!

Above all, I can’t emphasize enough that the bailout money goes to the customers, not the bank managers or equity owners. The bank leadership and employees will likely all lose their jobs, and the folks owning SVB stocks will lose their investment. By the way, we are all losers if we have money invested in U.S. equity index funds because SVB was big enough to be in the S&P 500 and certainly big enough to be in your U.S. Total Stock market Index. So we all bear the cost of the failure, and as equity investors, we should do so.

So, from a strictly economic point of view, the moral hazard problem occurs on the side of the depositors, not the bank leadership. Because depositors have coverage through the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), they may indeed “recklessly” deposit their money at weak under-capitalized banks led by a bunch of Yahoos. But realistically, what’s the alternative here? There is an asymmetric information problem. Even if all of us were finance and accounting experts, we don’t have access to non-public bank records. You can’t require everyone to be CFO-grade experts for every bank we do business with! With the $6.8t Joe Biden wants to spend annually, the government should regulate banks effectively and reliably so we can all concentrate on our own businesses. You know, to be able to pay for those taxes to fund a $6.8t-a-year government!

In defense of bailing out funds above $250,000

I’ve never had more than $250,000 at any one bank. I usually keep less than $2,500 in my checking account at Wells Fargo. Of course, I have more than that at Fidelity, but the money there is in index funds, so the failure of a brokerage does not jeopardize the investment because those funds are held in custody away from Fidelity’s balance sheet.

So, since I’m so clearly below the $250k FDIC limit, does that mean I couldn’t be bothered if large businesses lose their deposits in a bank failure? Of course not. As an economist, I care about the efficient functioning of the economy, and even though I don’t have a horse in this race, I find it unfair that the FDIC insures funds only up to $250k.

Should Chief Financial Officers divert time and resources away from financial planning at their own companies to monitor the health of the financial institutions they bank with? That’s indeed what the moral hazard talking-head clowns are telling us: according to them, retail investors should not be bothered about researching banks because we’re so dumb. But suddenly, businesses are such expert financial wizards that they can see through all the asymmetric information problems inherent in banking. Essentially, they are telling us that large business clients of SVB ought to have better insights into the bank’s asset and liability positions than even the CFO and CRO (Chief Risk Officer) at SVB. And the bank client’s CFO ought to have better insights than even the government banking supervisors, e.g., the Federal Reserve, who have access to a bank’s non-public data. Come on, let’s be realistic. Business clients face the same asymmetric information problems as retail clients. If mom-and-pop checking accounts are insured, then so should business checking accounts up to any level.

And what about the advice of spreading your funds to multiple banks? It works for retail clients but not for businesses. Let’s take a medium-sized company with 1,000 employees and a monthly payroll of $10m. That company probably has at least $20m in cash sitting in a corporate checking account to satisfy monthly cash flow needs. Will we tell this company that it should just spread its money over 80 different banks to stay below the $250k limit? And if the company gets paid by a customer, will it ask for 80 different checks or 80 different ACH transfers to go to those different accounts? If businesses operated that way, they’d be busier managing their bank counterparty risk than running their own affairs. And large firms like Walmart, Amazon, Apple, Exxon Mobil, etc., probably couldn’t find enough banks in the entire U.S. to spread their cash and stay below $250k at each institution.

So, get rid of that stupid $250k FDIC insurance limit! Effectively we already have done so after the latest two bank failures at Silicon Valley Bank and Signature Bank. Why not make it official? Nothing in the Diamond-Dybvig model says we should limit the deposit insurance. Quite the contrary, the implication from the Nobel laureates is that we will keep repeating Silicon Valley Bank failures if a bank has enough uninsured deposits from large business clients. So, please spare me the Moral Hazard platitudes!

Conclusion

Back in the late 90s in graduate school at the University of Minnesota, the 1983 Diamond-Dybvig paper was one of my favorite reads. The model is simple and intuitive yet offers wide-ranging and valuable insights. Contrary to public opinion, deposit insurance leads to more financial stability, not less. I think that the concerns about moral hazard are overblown. The benefits of deposit insurance clearly outweigh the concerns over moral hazard.

So much for this week. A lot of venting today, I know. But I hope you still enjoyed it! Happy trading through this volatile market!

Thanks for stopping by today! Looking forward to discussing this more in the section below!

Title picture credit: pixabay.com

Great post and you’ll send me down the path of reviewing Diamond Dybvig.

The ironic part about all the panic is the drop in treasury rates helps fix the underlying problem. If they hold through 3/31, bank capital will look better and hopefully some of these more troubled institutions take some losses on the portfolio in exchange for liquidity.

I talked to a small bank CEO yesterday, he reminded me that even banks who went into 2020 with 100% loan to deposit ratio were flooded with deposits and it had to go somewhere. Fortunately not every bank looked like SVB of FRC where deposits more than doubled at a time where the available investments were yielding sub 2.5%.

Thanks, Mr. Shirts!

That’s a great point. Maybe there is more then enough $$$ available now after the Treasury rally.

Wow, thanks for sharing that story about the small bank. Easy money always has some bitter aftertaste in the end. I hope, as you say, that other bank CEOs had a better hand in deploying those funds.

Thanks Ern for shedding some lights about the current banking situation.

Like you, I don’t have too much (direct) concern because we don’t hold that amount of cash in a bank account, and our shares are held in custody away from IBKR. FYI in Europe, the deposits are protected up to 100K Euros.

Nevertheless, it has an impact on the economy as people are now suspicious of the solvability of banks. No bank (even well managed) can sustain a bank run, and deposit insurance mechanisms are here to prevent people from taking money out of their bank. But where do people would keep their money if not in bank account? Cash under the mattress? Or maybe in Crypto as the Top 4 crypto have gained ~11% overall over the last week (and it is not an advice either).

Thanks!

Yes, crypto seemed to be the winner in all of this. Good for the sector because it had some bad luck on the solvency front (FTX, etc.). Let’s hope the people that pulled money out of the U.S. banking system and put in into crypto don’t lose it all in the next FTX or wallet hack.

Curious of your take on Baliji’s hyperinflation prediction in the next 90 days due to the large percentage of bank assets under water and speed of information in the digital age. I’ve always considered Baliji a thought leader on macro trends.

https://twitter.com/balajis/status/1636797265317867520?

It seems implausible, but frightening.

First: it’s not 40:1 odds. One is a probability. One is a ratio of prices. The two don’t have to be the same.

He offers a bet that he knows nobody will take. And claims that’s the proof that BTCC rallies to $1m. Not very credible. If anything, a banking crisis will be deflationary, just as 2008/9.

My prediction: Some people who rescued their assets out of the banking system and plowed them into BTC will lose their cash there in the next crypto exchange scam.

Appreciate the thoughtful commentary on the current situation. It doesn’t make sense for a business to spread out their checking accounts a million ways. Definitely a mixed bag, but fancy accounting didn’t help anyone…

Glad we agree on this. I prefer Frugally Reckless over Reckless Accounting! 😉

Thanks for the thoughtful right. It is a shame regulators didn’t catch this. I believe for banks too big to fail they have to mark to market to calculate capital ratios, which probably would have brought this to light earlier. Unfortunately the limit to be classified as too big to fail was raised to 250bln a few years ago, excluding banks like SVB. Any banks that need gov assistance to fail should probably be included in those stricter requirements.

Yeah, it’s always a two-edged sword.

I think the changes that came about the same time as the Trump 2018 tax law change didn’t really make a difference. Stress tests were rolled back and apparently the stress tests that were given to banks recently would not have been about any stress that killed SVB.

See here: https://www.wsj.com/articles/stress-testing-wouldnt-have-saved-silicon-valley-bank-fomc-federal-reserve-treasury-bank-run-signature-bank-1573ab77?mod=Searchresults_pos1&page=1

“But even if midsize banks had been subjected to the same scrutiny as large banks, it isn’t clear that stress testing them would have led to changes that would have prevented failure. Why? Because the tests asked the wrong questions. They failed to encompass the scenarios that ultimately led to SVB’s demise—large and rapid increases in interest rates.”

A few minor nits:

1. Due to its state charter and Federal Reserve membership, the bank’s primary regulators were the Federal Reserve Bank and the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (and not the FDIC).

2. The AFS/HTM securities classification system did not come out of the GFC and instead has existed for decades.

3. On Schedule RC-B of their Call Reports, banks report both the fair value and amortized cost of securities regardless of their AFS or HTM designation. The primary difference between the classifications is that on the balance sheet, HTM securities are reported at amortized cost and AFS securities are reported at FV. Any net unrealized gains/losses on AFS securities appear in the accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) component of equity capital (and usually partially in a deferred tax asset/liability). While significant unrealized losses in its AFS portfolio could result in a bank having little or negative reported equity capital, that does not make it “insolvent” from a regulatory standpoint. For regulatory capital purposes, the unrealized gains/losses that appear in the AOCI component are reversed when Tier 1 Capital is calculated on Schedule RC-R. Therefore, for most banks there is no change to reported Tier 1 Capital regardless of whether depreciating securities are designated as HTM or AFS (and thus no accounting trick in play to “hide” the losses from regulators).

Thanks for the accounting lesson! 🙂

1: I changed that. Thanks!

2: Sorry, didn’t mean to make this sound like it’s coming from the GFC. I know it’s a more general accounting principle. I will change the language in the post to reflect that it was used during the GFC, but of course not invented during the GFC.

3: Thanks for the explanation. Do you estimate the regulators knew that SVB is “economically” insolvent in today’s interest environment, but just not insolvent when using the letter of the law and how all those AOCI used in the sausage-making?

Yes, the regulators would be aware of all banks’ equity (book) capital levels, at least as of 12/31/22. All banks have to file quarterly, public financial reports which are commonly referred to as Call Reports. The first quarter filings are due by 4/30/23 and will include an updated look at securities depreciation and equity capital levels. From the regulators’ standpoint, the focus would be on the ratios referred to within the capital rules (e.g., Tier 1 Leverage Capital ratio, Total Risk-Based Capital ratio), which allow for the exclusion of the AOCI component. These ratios dictate the bank’s category (e.g., Well Capitalized, Adequately Capitalized) under the Prompt Corrective Action framework.

Thanks for explaining!

Shout out to the U of M, go gophers!

Yes, Go Gophers! 🙂

I will be back in Minneapolis this May for a conference in honor of Prof. Tim Kehoe. Can’t wait to go back!

It’s too bad no one in the media is questioning the Roth billionaire who yelled “fire” that contributed to this bank run. I think another issue was that they were looking for a capital inclusion too late. Had they got it done before they sold their bonds (sustaining the loss) it would have gone smoothly. Instead, they were looking for dollars and someone, somewhere alerted the Silicon Valley VCs that this outcome was a possibility. They then called their buddies and so on and so on. With 37,000 accounts holding $4.2MM on average, it was a powder keg. Too bad SVB couldn’t have discussed this with the FDIC (or the like) and described their position. Had they just kept the doors closed for a day or two, until they came up with their “rescue plan,” it could have been avoided or slowly unwound without panic. But in today’s world when 1/3 of the deposits are dried up via keystrokes (instead of lining up at the door), as you pointed out, anything is possible with even the best, most “secure” of them.

Good point. It would have been nice if that rescue package that was created for First Republic could have been used for SIVB to prevent all this mess in the first place.

“It’s too bad no one in the media is questioning the Roth billionaire who yelled “fire” that contributed to this bank run.”

Blaming the person who blew the whistle on an insolvent bank for problems of SVB’s own doing and from the lack of proper oversight by the CA and Fed regulators is not a “good point”.

Sounds to me more like someone breaking the 10th Commandment wanting to get in a shot at someone he doesn’t like…

And not even a good “shot” at that. I don’t recall Karsten ever once on this website suggesting that taxpayers using the rules of the tax code perfectly legally to avoid taxes is a bad thing. Quite the opposite, in fact…

Yes! The rules are the rules. If you accumulate 9-figures or even more in a Roth, you’re my hero!

Yeah, valid point. If the bank is underwater then you can’t blame the guy who starts the run.

Maybe the rationale was that as a bank it’s a profitable business and it would, over time, get to a positive value again. It would have saved us a lot of disruptions.

But you’re right, we can’t allow bailouts to become the rule. Otherwise we’d end up with a lot of zombie companies. Like in Japan and now in China.

For regular depositors who are married and/or who have kids, it’s pretty simple to add a POD beneficiary to an account which rolls up $250k per designation. IRAs are also separate. So if you are married with kids it’s pretty easy to get into a quarter of a mil range of FDIC coverage (but you’d want to discuss this with your kids so in case you died, the money is known to be going back to your spouse even though it might be in your kids’ names).

Exactly. I think married couples can then bring it to 4x $250k. It’s per person and probably also 1+1 each for checking and savings accounts. But not 100% sure.

For a married couple at a single bank:

Individual account for first partner – $250k

Individual account for second partner – $250k

Joint account – $250k

… for a total of $750. Not sure if you could get even higher with trusts, etc. See here: https://www.fdic.gov/resources/deposit-insurance/financial-products-insured/

Also noteworthy is SIPC insurance on _brokerage_ accounts including IRAs. See here for clean and simple example:

https://www.sipc.org/for-investors/investors-with-multiple-accounts

Nice! Thanks for the links!

ERN,

Excellent summary of the banking world and the recent runs. But why do we need to extend unlimited government (FDIC) insurance to businesses? Where is the 3rd party deposit insurance market? Certainly, if it were important to them, then a business could purchase private deposit insurance. Certainly the largest public and private companies (sales > $100 million) have the knowledge and capability to hedge or insure against this risk.

Now I understand the FDIC consumer need. Most individuals do not contemplate much less understand the issues involved.

Keep up the great writing.

I know. I wouldn’t be opposed to a 3rd party insurance scheme. But who would that party be? What if that 3rd party gets scrutiny? What party is large enough to bail out potentially the entire banking system? So, the federal government with the ability to create money out of thin air is probably the better-suited actor. But if someone has a good idea how to privatize it, I’m all for it.

In some sense Warren Buffett and BRK already plays the role of third party insurer. Banks can go to Buffett for capital — a “claim”, if you will — in exchange for whatever “premium” (equity, warrants, preferreds, etc.) Buffett negotiates. Of course, it’s tough to negotiate those premiums when you’re already making a claim! But how could anyone offer insurance when government offers it for free?

Warren Buffett is an imperfect insurer. He waits until the situation gets dicey to get a better deal from a desperate customer, like GS during the GFC. I would no rely that guy.

Funny that everyone says to turn off CNBC and financial media if you’re in the FIRE movement, but bloggers love to exactly that…replace the big financial media with

Yeah, if anything you should reverse what Jim Cramer touts every night on TV. 🙂

And now you can with the SJIM etf, no joke. It’s been one of the best performing assets since it was introduced a few weeks ago.

Heard about that too. It’s up in March! Amazing!

I wonder… what would it take to change this $250K limit? A literal act of congress? Or perhaps something less difficult? A quick google search reveals nothing, maybe I’m not using the best search terms…

I believe it is law. Specifically 12 U.S. Code § 1821 – Insurance Funds: https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/12/1821

Thanks!

Sounds like it takes an act of congress. But who knows, maybe the Supreme Court can find a way to read that into 14th Amendment. If you read between the lines, you know?! 😉

Why would they not tie it to inflation and not have to deal with raising it during a major banking crisis every couple of decades.

If they just tied it to inflation after raising it to $100k in 1980, it would be up to nearly $400k.

It would be a start to index to the CPI. But still not a big help for business clients.

Always enjoy your posts!

Keepthem comming and stay well!

Hanging in here. Thanks! 😉

One of the many irregularities that have come to light (and the Fed is reviewing) is that SVB did not have a CRO. So the run was engineered and coordinated by VCs, but the bank was poorly run with “leadership” pulling out of the stock and paying bonuses. The only good that can come from this mess is accountability and effective regulatory reform. And no limit to FDIC insurance.

I’m afraid the wrong change will come from this. But I hope the no-limit FDIC is part of the larger package.

Thanks ERN for another enjoyable, thought-provoking post.

Perhaps a basic question, but not sure I fully follow the opposite connection you were making between bank runs and the absence (or presence) of moral hazard: “Note that the absence of deposit insurance can cause a bank run. And deposit insurance can prevent a bank run. It’s the opposite of moral hazard!”.

I think of moral hazard as the incentive for bank CEOs/leaders to take risks with depositors’ money to increase their bank’s share price. If I’m more likely to be shielded from a bank run due to the presence of deposit insurance, doesn’t my incentive to take larger risks as CEO go up?

The business model of a bank is to take certain risks. Banks take short-term deposits and lend them out as long(er)-term assets to make money off the slope of the term structure and credit premiums. That is desired. And deposit insurance saves banks from being railroaded by having to liquidate illiquid assets at fire-sale prices.

Deposit insurance doesn’t and shouldn’t save a bank from making bad investments that push the bank into insolvency even in the absence of Diamond-Dybvig model illiquidity effects, like investing in questionable/risky projects (S&L Crisis), going way too crazy on the yield curve speculation without hedging duration effects (SVB), etc.

Is there any sense in keeping brokerage assets within the $500,000 SIPC insurance?

I don’t. My funds and preferreds are all held in custody. I don’t think I’d lose money if Fidelity goes under. And Fidelity won’t go under anyway.

For me, SIPC may be more important in case of fraud than a firm like Fidelity going under. I do wonder about how things play out with index funds/ETFs. For example, say Fidelity holds shares of SPY on your behalf. SPY is a basket of shares of different companies, and that basket is actually held by State Street. What if there is fraud at State Street? I don’t know, but I do sleep better keeping large index fund positions spread out between individual brokerage accounts, joint brokerage account, IRAs.

There is no fraud at STT. I would trust STT and BK with my money. I trust them more than the government.

Perhaps the reason we can’t go above $250k for FDIC insurance is that a blank check law could potentially force the government (which has a budget and a debt ceiling) into sudden insolvency or violation of budget laws after just a few banks failed. Yes, the government can print money, but it would take an act of Congress akin to what happened in 2020 to bail out a bank panic born from trillions of dollars in asset losses. Could the US bail out all its banks to the full amount originally deposited while simultaneously fighting a war, dealing with a disaster like the California Big One, dealing with a pandemic, or while in a state of demographic decline like Japan?

For the same reason, it’s hard to imagine a private insurance company big enough to insure against America’s bank runs. Some reinsurance firms can absorb a hurricane, but even those have never cost more than $125B. Such a firm would need trillions in reserve. Plus, any such firm’s reserves would have to be somehow invested counter-cyclically, so they couldn’t be knocked down at the same time as the banks.

Also, I think a bank run could happen even with, say, a $5M FDIC limit. A few very large corporations with, say, 20M, 30M, and 15M in their accounts could flee and push most small banks out of compliance with their ratios, even if such a bank had hundreds of thousands of middle class checking accounts with $2,000 each. The system wasn’t built for these big fish!

The solution is that banks must be regulated to a very utility-like existence, and depositors over FDIC limits must be required to pay for supplemental insurance, or at least a tax for contributing to financial instability.

Yet we keep going through cycles of deregulation, crisis, regulation, and then repeat. The US banking system was stable for several decades after the Glass-Steagal Act, but then the bank lobbyists had it repealed. Then we had the GFC. Then Dobbs-Frank. Then the bank lobbyists had that repealed for all but the biggest banks.

I can see the future: Next we’ll get another bank regulation bill that will be functionally repealed in 5-10 years.

No good solutions. Regulating like a utility is probably the worst, considering the incompetence of our government.

The SVB failure has nothing to do with the repeal of Glass-Steagal. SVB invested in Treasuries, the most conservative and safest asset possible. Dobbs-Frank wasn’t “repealed for all but the biggest banks” either. SVB was no longer subject to the stress tests, but what would have been the stress test? A credit event. SVB would have passed that stress test with flying colors because it invested in the safest asset, with no credit risk.

So, the problem is not a lack of regulation. The problem is that no regulation can foresee the next crisis. Regulation always tries to solve past crises. The same reason you still have to pour out your water bottles at the airport security check. Totally useless. But our stupid government insists on it. Banking regulations fail in the same way.

WRT the “regulate them like a utility” and the “unlimited deposit insurance” objectives, I don’t know if we can have one without the other. The FDIC is one thing at a $250k limit, but it’s a whole other beast with no limit. A limitless FDIC in the face of a major economic catastrophe could conceivably swallow much of the economy, create a currency crisis, or become a government program bigger than Social Security or Medicare. It could cost more than a major war, require money-printing to operate, override the debt ceiling, and set up an Argentina-like debt trap. The damage to bondholders from the rate hikes is in the trillions of dollars, and an unlimited FDIC would essentially involve taxpayers taking on that burden from the bondholders.

Taxpayers and the politicians will eventually demand some guardrails if they are on the hook for bailing out rich people and corporations who piled into banks that would be illiquid in the event of a few % in rate hikes.

I suspect the eventual solution would look something like this:

1) An AI-powered application for corporate treasurers that can open accounts at numerous banks, set up hundreds of FDIC-insured accounts, and allocate deposits and withdraws across the accounts. Employees would receive their pay from any one of these accounts, and the complexity of juggling all those accounts would be handled by the AI.

2) New categories of treasury bonds, with an instant redemption or variable duration option, just for banks.

3) New stress test rules requiring banks to meet certain requirements in the event of a 2022-2023 scale series of rate hikes (i.e. interest rate risk).

The Diamond-Dybvig model recommends deposit insurance. There is no advantage and only disadvantages if you limit the level of insurance.

Also, the government isn’t on the hook for the entire insured amount. There are often enough assets to satisfy a significant % of the deposits, just not exactly 100%. So, considering all the other nonsense the government spends money on, there should be enough resources for this. Remember: the idea is to provide insurance so that you never need it.

But we have that already. Banks are already heavily regulated and supervised.

That would invalidate the term premium. Sure, you have no duration risk. But you also have significantly reduced income.

Yep, and then everybody will be caught off guard again by the 2027 banking crisis. Rinse and repeat.

Excellent post, thanks for the analysis. I agree that the $250k FDIC limit made very little sense. And with the government bailing out the depositors, it looks like in practice that change may already have been made.

On a personal note, my second company had far more than the $250k sitting in a checking account at SVB the day of the bank run. They had just closed a fundraise and hadn’t had an opportunity yet to distribute the funds into different accounts. So I’m quite pleased that the FDIC is making depositors whole. If that hadn’t happened, the company I poured my blood, sweat, and tears into could have disappeared overnight.

Question for you: I’ve seen a lot of negative sentiment recently around the aggressiveness of the Fed’s rate hikes. But I can’t think of any alternatives. Hyperinflation perhaps? It’s been more than a decade since I was last studying macroeconomics, so perhaps there are other ideas about how to regulate the economy that I just haven’t been privy to.

Thanks for sharing that experience. People will call foul due to Moral Hazard, but you as a small business owner don’t have better information about a bank’s health than a mom-and-pop depositor. So, yes, you deserve FDIC insurance, up to much larger amounts than just $250k.

The Fed is between a rock and a hard place. Had they paused on 3/22, people would have panicked. Now they raised once more and that will likely be it.

But just for the record, the Fed raised rates way too late. This is the problem they created themselves. They could/should have raised more gradually in early 2021. Would have worked out much better.

“But just for the record, the Fed raised rates way too late. This is the problem they created themselves. They could/should have raised more gradually in early 2021.”

In hindsight this is very clear, but in the moment it was very hard to prove that inflation that was happening wasn’t transitory. Even at the the time of the Dec ’21 rate hike, the PCE inflation measure that they look at was still only in the 4.x% range.

IMO the bigger blame should congress who kept showering people making six figures with stimulus even after the vaccines were out and the stock market and jobs market was red hot in 2021. Even 3 years later, student loan payments for college graduates who tend to be higher earners are STILL on hold which continues to fuel inflation. I know the student loan crisis is a whole different issue, but this isn’t a sustainable long term solution for that IMO.

*Dec ’21 fed meeting, not rate hike

Agree 100%. There’s a lot of blame to go around, and fiscal policy was many times more reckless. Also, as you state, monetary policy couldn’t have been 100% sure it was time to hike rates in 2021 but it was pretty clear that fiscal policy was completely out of control. And still is, by the way.

Suggesting that small businesses should be allowed to have a larger limit ($20M, say) is one thing. I’d probably be good with that. But you still haven’t said who should pay for your proposed unlimited deposit insurance.

OTOH if the big fish had some skin in the game – say only 90 cents on each dollar was guaranteed, and that 90 cents could be received from the FDIC within 7 days of a bank closing – then that’s something I could probably go along with. And the incremental cost of the insurance for that kind of approach I bet would be an order of magnitude lower.

Again: D&D’s Nobel-winning research: there should be no cap.

There is a benefit of that, and society should pay for it, so, yes, the FDIC premium would marginally increase.

I have a problem with your suggestion that “of course” all deposits no matter how big should be bailed out.

FDIC deposit insurance historically has been paid by premiums that banks and savings associations pay for deposit insurance coverage. Pretty sure that these premiums didn’t cover unlimited size of deposits, but rather were (are!) based on the deposits not exceeding the $250K limits Pretty sure taxpayers paid for the bailouts that exceeded the $250K limit. Pretty sure interest received by depositors is somewhat lower to reflect the cost of this insurance.

Also pretty sure that to make your suggestion “the rule” would require further increases in the insurance premiums.

I also don’t fully accept your argument that large companies would have to keep their money in 7.000 different accounts. The point is that it’s efficient for large companies to keep their money in banks that are low risk, and figure out which ones are and which ones are not, and that people with skin in the game will in aggregate do a better job than bureaucrats without such skin (as you yourself noted re regulators not losing jobs or pensions here). But here at least I acknowledge that it’s at least a valid thing to consider.

There’s rarely such thing as a free lunch.

(Feel free to correct anything above I got wrong)

We don’t disagree on much. In a perfect world, I agree that a private entity could do the job of banking regulation. Everybody will be on their best behavior, and we won’t have bank failures.

But we don’t live in a perfect world. As I wrote, even a CFO of a large company will not be able to figure out which banks are secure and which aren’t, so short of spreading your cash to 1000s of different banks, you will always have a residual risk. First Republic Bank looked like a safe bank to most people, even very sophisticated ones. Until it shut down! So, how exactly are we supposed to distinguish between “banks that are low risk” and those that aren’t? What CFO has better information than the material nonpublic information that the SF Fed had when they missed the warning signs?

Of course, the banking industry could create a self-managed quality control board with well-paid, competent bank examiners (sort of the opposite of the SF Federal Reserve ones) to have access to all that material nonpublic information. There are multiple problems, though:

1) how do we enforce the firewall and make sure that none of the material nonpublic info gets sold to hedge funds?

2) If that new entity has no skin in the game, we’re back to the same issue the hapless SF Fed examiners faced. They will probably also watch TikTok videos and miss the warning signs. But having skin in the game would again imply that this private initiative provides deposit insurance.

3) How do we go from a healthy bank to a non-healthy bank? How will this new entity downgrade a bank from safe to unsafe? Will this not create a bank run? Are there political pressures to not downgrade a bank with enough political connections? I also remember Moody’s/S&P/Fitch giving investment-grade ratings to junk bonds in 2007, due to their backdoor business connections to Lehman, AIG, etc.

And I would like to remind everyone again: The Nobel-Prize-winning research by Diamond & Dybvig recommends unlimited deposit insurance. Not a $250k cap.

Thanks for the above. I don’t claim to be an expert on banking regulation.

I would not advocate for an “independent” quality control board. But just as there are analysts for everything else on Wall Street, there can be analysts for ordinary banks that take deposits. There are the bond rating agencies. Yeah, you gotta pick the better evaluators to listen to, not just go with the same info everyone else does. That’s the point of competition and a free market. And large companies have multiple options (Treasuries, MMFs, TIPS ladders, …) for most of their money most of the time that smaller businesses do not.

To the extent that banks are special it’s because Fed regulation and practices have made them so.

But I guess my biggest problem with your simple assertion that there should be deposit insurance on all deposits is your dismissal of Moral Hazard. Skin in the game *does* matter. Moral hazard – heads I win, tails you lose – is a real thing. I *never* agree with Elizabeth Warren, but I agree with her that bank executives (benefiting from FDIC deposit insurance, and implicit bailout guarantees) should be subject to multiyear clawbacks when poor risk choices go sour. Bank Boards, too. It’s clear that SVB ahead poor incentives for executive compensation.

We saw moral hazard with the Asian contagion and Mexico crisis bailouts, where GS got bailed out on their investments for 100 cents on the dollar. We saw it in the financial crisis, with again so many being bailed out at 100 cents on the dollar.

We see it now with “systemically important” banks that are too big to fail, as part of a cure-largely-worse-than-the-disease Dodd-Frank which rather than fixing too-big-to-fail entrenched it, virtually requiring bank consolidation, and entrenched at least part of the moral hazard.

Sorry, any bank that is too big to fail should not get still extra benefit from cheap deposits backed by full deposit insurance while maintaining ridiculously low equity ratios. Unless they wanna go back to Glass-Steagall regulations where traditional deposit and loan highly regulated banking are all they do.

So even if you are right that “unlimited” deposit insurance would be a social good (and a Nobel prize for theoretical work is not the be all and end all to me, no matter how valuable the contribution to our system of knowledge), it seems to me it’d both be a lot more cost effective, and actually do more social good, if there were skin in the game where the guarantee above a certain amount was only 90 (95? 98??) cents on the dollar rather than 100. Full deposit insurance versus none above a certain level need not be the only two options.

Thx for listening 😀

I’m glad we agree on the view that a new “quality control board” is unworkable.

Are you kidding? We have those already. All prominent banks that failed were publicly traded banks: Silicon Valley, First Republic, Signature, and Silvergate. There may be some exotic, non-publicly-traded banks but they tend to be small enough not to create any systemic issues. All the equity analysts were unable to see the warning signs. In their defense: they have no material nonpublic information. So my question to you is still: how can independent analysts with less information better predict banking failures than Federal Reserve banking supervision employees who have access to all top-secret proprietary information of the bank?

Moral hazard:

Sadly, the term “moral hazard” is one of the most misunderstood terms in economics. This misunderstanding of moral hazard leads to these cheap platitudes and cliches you mentioned. Please read my blog post again. Deposit insurance creates no moral hazard in the US banking sector. As a bank employee, if you screw up you lose. Every single bank failure that’s covered by the FDIC wiped out the equity and wiped out the jobs and bonus pools for employees (and not just the culprits but all employees). There is no moral hazard due to deposit insurance on the side of bank leadership, employees, and equity holders. The FDIC does create moral hazard in the form of depositors haphazardly depositing funds in banks when they have no clue how healthy said bank may be. And the more troublesome Moral Hazard issue: the bank examiners at the SF Fed that were asleep at the wheel? They all kept their jobs. So that they can mess up the next bank, too. That’s the true M.H. issue!

As you wrote earlier, we do agree on more than we disagree. Partly we have a terminology problem. But partly we do still disagree when you state categorically that “Deposit insurance creates no moral hazard in the US banking sector”.

Moral hazard means that people are incentivized to take undue risks because they believe they will not bear the consequences of those risks. Where do es this occur in the context of deposit insurance:

1) Bank executives – like specifically at SVB – take undue risks (here, simple duration risk) and reap rewards in higher bonuses and the ability to sell their options/RSUs before they leave the company without fear of that past year compensation being clawed back. So they have incentive to gather more deposits and invest the proceeds unwisely (higher risk than they otherwise would/could). This noted, I *do* agree that the moral hazard here is lesser than a) the moral hazard of too-big-to-fail with the big banks with complex opaque other investments, and b) that this risk for “simpler” banks is lesser than the moral hazard of depositors (next).

2) Depositors have virtually no incentive to deposit their money at less risky banks, and are free to chase yield or choose convenience over safety. Surely this is beyond dispute. We agree that for small investors the value of overall stability is generally worth living with this moral hazard. I agree with you that we could/should make the insured amounts higher, and probably should be substantially higher for small businesses [in aggregate for each SMB, not per account/bank, IMO].

But if you change to completely unlimited deposit insurance at 100 cents on the dollar, then this moral hazard increases substantially, and especially absent the *cost* of said insurance, it’s hard to state categorically that the supposed benefit in terms of system stability is worth this vastly increased moral hazard.

I find your position especially curious given that we agree completely that regulators are NOT the answer here. I quibble only with your use of the term “moral hazard” here; to me, this is a crystal clear example of lack of skin in the game. Regulators have no money invested, and as we’ve seen have no risk to their jobs, nor much of any risk to their reputations when they fail (and, it should be noted, would likely face heavy political pressure and risk to their jobs if/when they *did* take a hard line).

(Admittedly, the concepts overlap: moral hazard means insufficient skin in the game in terms of risk/reward. Regulators have literally NO skin in the game.)

Since regulators alone are surely not the answer, and since costs *do* matter, then letting the free market work as much as possible – competition, risk/reward, self-interest – is surely better than piling more costs on taxpayers and allowing unlimited 100 cents on the dollar deposit insurance, which would only increase the moral hazard of removing depositors’ skin in the game entirely.

Again, you’re not an economist, and it shows. You’re throwing around big names and you’re sloppy with the meaning of economic terms. The problem you describe is called the “principal agent problem” and it has nothing to do with deposit insurance and moral hazard. It’s not even specific to banks either; remember Tyco, Enron, Worldcom, etc.? CEOs of all companies (banks and non-banks) do all sorts of stuff that benefits themselves short-term and screws over shareholders in the long term, and that’s the reason we have Boards that closely monitor CEOs and kick them out when they misbehave. However, a bank CEO is not insured by the FDIC, and thus is not subject to Moral Hazard. It’s the depositors. If the bank CEO is at the helm when the bank fails then the bank CEO will lose his bonus shares his job and his reputation. Simple as that.

Correct. And we can’t require mom-and-pop depositors, or even sophisticated depositors, not even CFOs of multi-national corporations, to waste their valuable time on doing their own banking supervision exercise. That’s why have the Fed and state regulators. Moral Hazard on the part of the depositors is a non-issue as long as we have decent banking regulators.

And again: the Fed employees who screw up are the worst Moral Hazard problem. These guys keep their jobs, and pensions, etc. even after sleeping at the wheel.

https://www.ft.com/content/02ff2860-2d5b-4e21-96af-cef596bff58e

Details of the moral hazard here with SVB. And to the extent you believe the CEO Becker *did* care about his reputation in Silicon Valley or the safety of his customers’ money, you can be darn near 100% sure deposit insurance was a huge moral hazard here: do you *really* believe he would have taken that much duration risk if his customers risked having their deposits wiped out by his bets?!?

To repeat, the existence of deposit insurance *is* net a good thing, and I don’t dispute your premise that we would likely be better served with more of it than we have now, not less. But to suggest there is *no* moral hazard involved with it at all is, imo, not correct.

Again: it’s not M.H. It’s a principal agent problem. And again: bank execs are not insured by the FDIC.

And for full disclosure, I don’t subscribe tp the FT, so I didn’t read the article. If my worst fears are realized that even journalists at the FT are so economically illiterate that they call this issue Moral Hazard and not by its real name, then I won’t be subscribing to the FT anytime soon.